Arcadia Magazine Winter 2025: Being Intelligent About Artificial Intelligence

At Arcadia University, an artificial intelligence-powered chatbot acts the role of a recalcitrant patient, providing Physical Therapy students plenty of practice for the real deal in clinical rotations.

In a business writing course, students use a bot to write a cover letter for a wish-list job and then critique the result.

Meanwhile, students in AI for the Ages use ChatGPT and a range of other AI tools to simulate building a civilization, all the while experiencing firsthand the promise and perils of a technology that seems to be everything everywhere all at once.

“You can’t ignore it,” says Marianne Miserandino, PhD, a professor of Psychology and Arcadia’s inaugural AI Fellow at the Center for Teaching, Learning, and Mentoring (CTLM). “This is the tip of the iceberg.”

Across Arcadia, artificial intelligence (AI) is making its voice heard—sometimes literally. Many faculty, students, and staff are exploring and using ChatGPT and its brethren in all sorts of ways, both inside and outside the classroom. AI is helping students brainstorm ideas, assess business ideas, simplify complex concepts, study for exams, and figure out what to make for dinner from random ingredients in the fridge. Faculty also are using bots to create abstracts, refresh lesson plans, write administrative emails, and yes, figure out what to make for dinner from random ingredients in the fridge.

“AI is highly impacting the world of work across all disciplines and fields,” says C. Edward Watson, PhD, vice president for digital innovation at the American Association of Colleges and Universities in Washington, D.C., and co-author of the recent book Teaching with AI: A Practical Guide to a New Era of Human Learning. “Most university leaders, anecdotally, recognize they need to build AI instruction, AI literacy as a learning outcome, or AI competency within the curriculum. The next thing that has to happen is faculty buy-in.”

According to Tyton Partners, an investment banking and consultancy focused on the education sector, the adoption of AI technology among college educators is growing significantly. In a June 2024 survey titled “Time for Class: Unlocking Access to Effective Digital Teaching & Learning,” 36 percent of the instructors who responded are regular users of AI tools—up from less than a quarter in fall 2023. “As the world moves toward a place where generative AI is embedded in education and the workplace,” the report said, “institutions must adapt to increase the value of students’ education.”

Arcadia is working through that adaptation across the University: Folks are drafting AI policies, offering AI workshops, and exploring AI tools. The University, like many colleges, is figuring out if the technology that exploded on the scene in fall 2022 with the release of ChatGPT is boon or bane to higher education. It is a complex conversation over a technology that uses a large-language model to respond to requests or prompts, and in seconds, generates text, images, video, and other data. But the instant response comes at a cost, including huge energy consumption. (According to a Goldman Sachs report, an AI query uses 10 times the electricity of a traditional Google search.)

While Miserandino allows AI is not a panacea, as once thought, she continues to take the approach that educators need to learn how to teach with AI rather than against AI.

“Let’s suggest AI is not the monster, not to be fought or banned or avoided, but really an opportunity to do more of what makes us good teachers,” she said at a September CTLM Lunch & Learn on AI use and its future at Arcadia. “How might AI up our game? What does AI make possible for us? What does AI make possible for our students?”

***

In many ways, AI is like the Wild West—anything goes. At Arcadia, professors across departments are finding a variety of ways to tame the technology and incorporate it into their courses. Some are dabbling, a few are diving head first, and many are landing somewhere in between.

Art and Design Professor Carole Loeffler says she’s a fan. In her first-year seminar Textiles Stories this semester, she showed her students how to brainstorm project ideas via ChatGPT. As an example, she asked the bot to tell a story about a blanket her grandmother gave her. In seconds, it did just that. “We’re not going to grab that,” Loeffler, also the assistant director of the Honors Program, says she told her class. “But we’re going to use that to get the gears going in our brains and how that can inspire us to write our own stories.”

Tom Berendt, PhD, an adjunct assistant professor of Religious Studies, has come around to AI. “I felt very strongly that I didn’t want to take a Luddite approach, where AI is all bad,” he says. “AI is the future, even if we don’t like it, even if we’re scared of it, even if it’s going to impact critical thinking. The reality is that in the next year, five years, definitely 20 years, most students are not going to be writing papers by themselves. They’ll be utilizing different software to create their arguments.”

This semester, he’s shifted from asking students to avoid using AI for assignments in Introduction to Religious Studies to allowing it, as long as students cite it. He even used a bot to create colorful, idol-like images of Taylor Swift and John Lennon (below) for his lecture on popular culture as a form of religious expression. “I’m just sowing the seeds,” he says. “It’s not that I’m truly excited about AI. I see it as a less apocalyptic event.”

For Physical Therapy student Rachel Polk ’25DPT, from Lexington Park, Md., the use of AI has proven “invaluable,” not to mention “really cool,” she says. Students use ChatGPT for feedback on patient assessment notes and to role-play.

In one scenario, students take a history from the bot patient and formulate a plan of action, getting real-time feedback on technique. “You didn’t introduce yourself” or “You sounded empathetic,” the bot/patient might reflect, appearing eerily realistic. In another, they deal with a difficult client who refuses to do her exercises. In both instances, the chat transcripts are sent to the instructor along with reflections from students on how it went.

“It helps me form good thought processes,” Polk says. She and her study buddies have incorporated AI into exam prep, asking the chatbot to generate patient cases that they then use to practice diagnosing conditions, and as a result, have seen better scores. “You can memorize all the facts left and right. But as PTs and PT students, what we have to do is apply them to a clinical application. AI was a huge boost.”

Kathleen Fortier ’04, ’07DPT, ’11MBA, assistant director of clinical education for PT, researches how technology impacts student learning. She has found that AI can help students feel more comfortable navigating instances of uncertainty, such as when a course of treatment isn’t obvious and falls into the “it depends” area. The scenarios give students low-stakes interactions with “patients” early on and quality feedback very similar to a clinical instructor, says the assistant professor of practice. “It’s almost this unbiased third party that seems safe,” Fortier says.

In the School of Global Business, Laura Fitzwater, an adjunct instructor of English, created a new lesson this semester to introduce AI to her Business Writing students: Ask ChatGPT to write a cover letter based on the responsibilities of a job you might want.

“Wow, it sounded really good,” Business Administration major Jack Quigley ’27, of Elk Grove Village, Ill., says of the letter the bot generated for an insurance agent position. “It spits it out in a matter of seconds. It didn’t sound like a robot wrote it.”

Fitzwater also asked students to prompt the bot to analyze the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) of their online businesses, the main project for the course, and compare it to the assessment they had already done. ChatGPT, she says, gave many of them additional insights.

“It was eye-opening for them,” she says.

Quigley found that the bot’s analysis got him thinking beyond marketing to the financial and investment aspects of his team’s hockey and golf company. “Obviously, you can’t have it do your homework for you,” he says. “But why did I take 30 to 40 minutes to do the SWOT [analysis] by myself? ChatGPT does it–boom!–in five seconds.”

***

Arguably, the essential question that educators must grapple with is this: Why should students invest the time and energy to learn something when a bot can do it faster and likely better?

Katherine Moore, PhD, an associate professor of Psychology who studies cognitive science, gives one answer: “A college education is about learning. The learning can’t happen without the practice and struggling and doing. That’s why I feel like it’s hard to find great uses for large-language models in the classroom. It has to be done very carefully.” She makes the analogy to the introduction of calculators to schools. “You don’t give calculators to kindergarteners, because they need to learn arithmetic.”

But when it comes to students who have mastered concepts or to experts like herself, that’s a different ballgame, Moore says. She has used ChatGPT to generate tones for an auditory perception experiment—saving her the time of writing computer code, and one of her senior thesis students uses Consensus, an AI research assistant that delivers science-backed answers, to keep up with the latest literature on his topic. “The way he describes it,” Moore says, “this has helped him get to understanding faster.”

Education professor Peter Appelbaum, EdD, takes a different view. In a paper with the whimsical title “Stochastic Parrots, Policies, Octopi Who Pretend to Be Human, & Dancing Robots,” published in February 2024 in the Journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Curriculum Studies, he argues educators “are worrying unnecessarily about AI taking over, because it’s not a form of intelligence. It’s a language model, using the likelihood of what words might come next. It’s a statistical process. It’s not thinking in any way.”

Given that, Appelbaum lets students in Rethinking Gender and Sexuality Education use the tech for project ideas and even to revise the required biweekly reflection. He doesn’t consider the latter plagiarism, despite his students expressing worries, because the class is not a writing course and the assignment is based on opinion. But there are limitations, Appelbaum says.

“ChatGPT seems to be not aware of certain kinds of intersectionality or the importance of Black feminist theory,” he says. Only after repeated refinement of the prompts, some seven tries, did the bot suggest viable project ideas for his class, he says. “We can use it. But you need to bring knowledge to it, this critical perspective.”

Recently, Miserandino used ChatGPT to find a new way to teach about the controversial Milgram Shock Experiment that studied obedience and disobedience to an authority figure. Instead of the usual readings, which her students considered long and difficult to master, ChatGPT suggested pulling quotes from the study subjects on how they felt during the experiment and having students organize them by themes and then linking them to ethical principles. “It came up with a fantastic exercise,” she says.

But here’s why Miserandino continues to urge caution. When the bot pulled the quotes, it made up one and missed others. “AI can give you answers or thinks it’s giving you answers,” she says, “but it doesn’t have the wisdom that a scholar working in a field has.

“It’s up to faculty to curate,” she continues. “What are the learning objectives of my class? What is it I want students to learn and demonstrate and how can I best get them there? Maybe AI can help. Maybe not. Each field needs to figure out what that is and what it looks like for your major, for your discipline, and then for your classroom.”

Over recent months, Arcadia has taken numerous steps—both as an institution and within individual departments or classrooms—to figure some of that out. A group that included Miserandino and faculty from Computer Science, Education, Landman Library, and other areas went to a conference in 2023 to learn more about AI in education. Then Valerie Green, EdD, director of Digital Learning Services, and Miserandino then built a resource-heavy website, AI@AU.

CTLM also has put on its website sample AI policies and has sponsored a series of workshops, including one with keynote speaker Jason Gulya, a Berkeley College English professor who advises colleges on ways to leverage AI. CTLM plans to host more workshops, including one that tackles concerns over plagiarism, and is organizing a task force to more systematically assess the impact of AI on academics, including creative uses and ethical and environmental challenges.

“We’re going to be okay,” Miserandino says. “What makes for good teaching and good learning has not changed. Technology merely helps us in this process.”

***

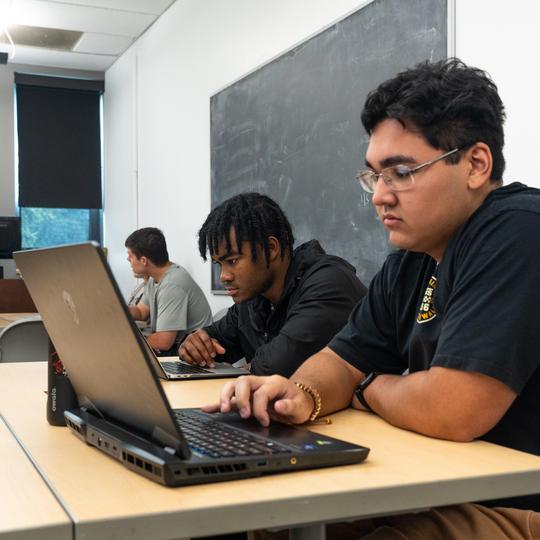

On the third floor of Brubaker Hall on a recent Monday, Associate Professor of Marketing Raghu Kurthakoti, PhD, who also chairs the School of Global Business, asks students in his Advertising and Sales Promotion course to take a few minutes to create an ad using ChatGPT. “The prompt is very, very critical,” he emphasizes. “Play around and see what it comes up with.”

Students use AI to brainstorm ideas for specific brand sponsors for the Olympics, streaming services, and automobiles. They quickly realize that general prompts get generic responses and images. But when students ask ChatGPT to consider the target audience, the approach (rational versus emotional ads), and the look, results improve. They then analyze the pros and cons of the AI ads, talking about the ideas sparked, the biases and stereotypes advanced, and the complete misses.

“That’s the discussion I want to have in class,” Kurthakoti says, “and see if students understand the ethics of it.”

It’s a turnaround for him. Just last year, Kurthakoti was discouraging the use of AI in his class. Then a couple of students used a bot to fill in journal entries about industry ads. (He could tell from the advanced concepts cited that he hadn’t taught.) “I didn’t anticipate that,” he says. “So I thought, let me make AI a formal part of the course and teach them how to use it better.”

He also updated his AI policy, with the help of ChatGPT and Gemini, from a couple of sentences to a one-and-a-half-page treatise that covers instances of allowable and not allowable uses of the technology. “It’s better to be long and repetitive,” he says, “than leave lots of things up in the air.”

One floor down in Brubaker, AI looms over every decision students make as they build civilizations in Adjunct Physics Professor Robert Miller’s class AI for the Ages.

Called an open-world scenario, students divided into teams create and manage their colony, using AI tools to run the complex simulation that includes buying land, making and selling commodities, managing finances, and even waging war and conducting diplomacy. At the same time, Miller informally lectures on AI’s history and impact on society, and by the end of the simulation, he will have the class discuss the role AI played in the decisions made.

Pre-dental Business Administration major Simon Abdullah ’26, of Greenville, Del., already uses AI to study, asking ChatGPT to explain concepts to him as if he were a fourth grader. He took the class, which he describes as fun and creative, to better understand AI, because “it’s such an exciting and rapidly growing field that is changing how we live, work and do everything in the world now.”

Morgan McEntire ’25, a Public Health major from Bath, Pa., allows she was skeptical about AI’s usefulness at first, but now sees the potential. “Exposure to the different types of AI,” she says, “sets you up for success in the future.”

Miller couldn’t agree more.

“This is the next big technology leap that’s not going away,” he says. “Kids need to know how to manage data, how to think algorithmically. They need to know the ethics.

“This class,” he says “is opening the door.”