March 31–April 27, 2011

Arcadia University Art Gallery

“Keith Haring: Subway Drawings,” celebrates the 30th anniversary of the emergence of these seminal works by this Pennsylvania native (born 1958, in Reading). Critical to understanding Haring’s brief career and his efforts to connect pop culture, fine art, social activism, and commercial practices, the subway drawings have proven to be increasingly influential, and especially relevant to street artists working today.1

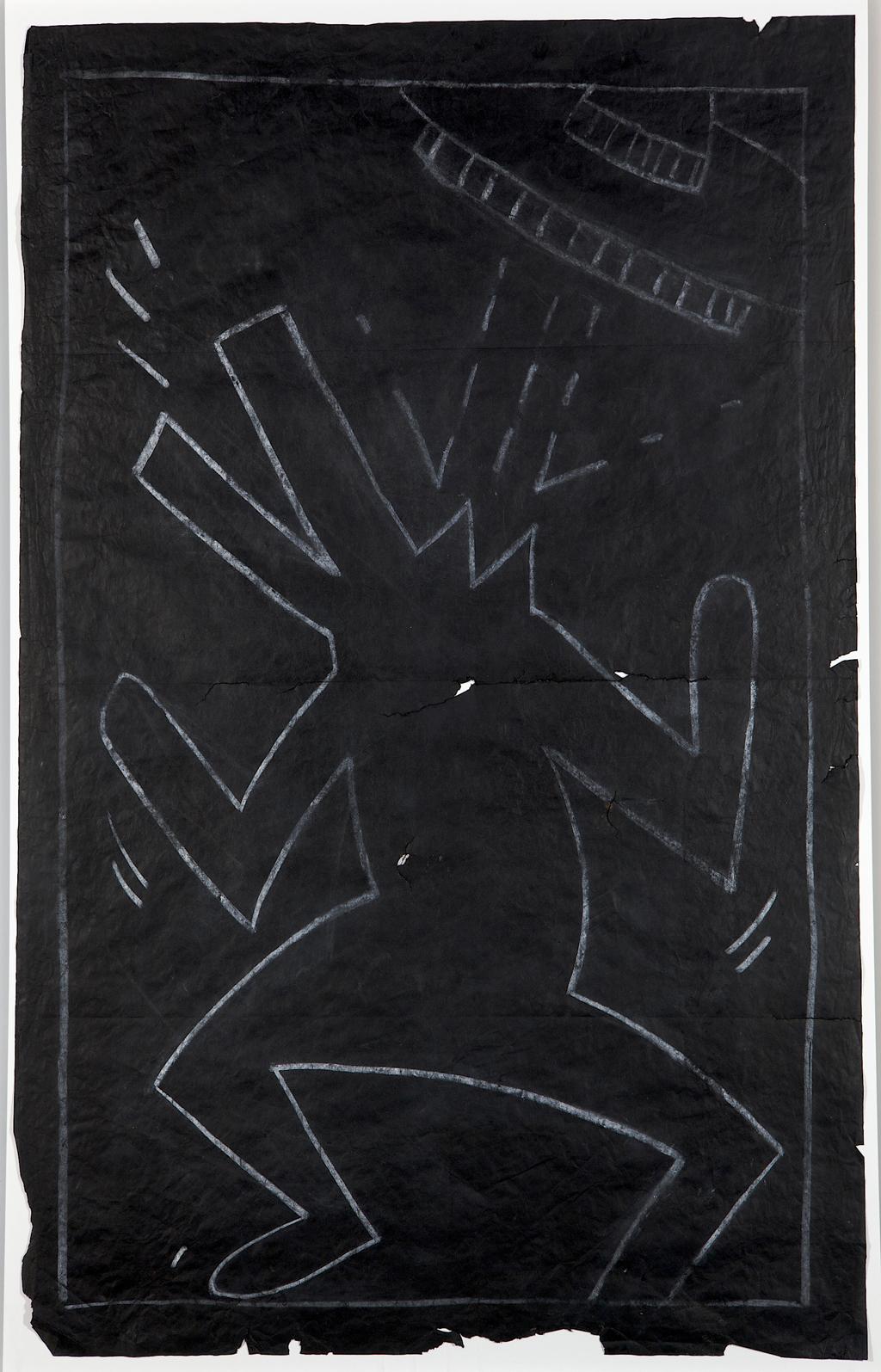

Untitled (UFO and dog), ca. 1980 - 1983, chalk on black paper, 48.75” x 32”, Collection of Justin Warsh, Keith Haring artwork © Keith Haring Foundation. Photo credit: Aaron Igler, Greenhouse Media.

The twelve examples on view date from 1980 to 1983, the most prolific period of an unprecedented effort that generated thousands of drawings, all executed with chalk on sheets of black paper used to cover un-renewed advertisements in the New York City subway. The project began serendipitously when Haring noticed one of these blank panels in Times Square station. Realizing that the black sheet might be an ideal surface on which to mark with chalk, he immediately went above ground to buy some. The resulting activity, something Haring first considered a “hobby” practiced while waiting for the subway, became what he later called a “responsibility” that could consume hours a day once the drawings found their audience.2Maintaining the project remained important for Haring through 1985, long after he had achieved international critical and commercial success.

Often produced in front of spectators, which might include subway police that could ticket him for “criminal mischief”, the works appeared at a rate of sometimes 40 a day. Rarely tagged or defaced by others—when not torn or cut from their locations by admirers—they would inevitably be covered by new advertisements. The routine loss of the drawings, in fact, became an incentive for their replenishment and a catalyst for continuous reinvention that fueled Haring’s early work. Kermit Oswald, the artist’s childhood friend and sometimes collaborator, referred to the subway as “a nursery, an incubator that forced his hand.” 3 While many of the drawings were documented by photographer Tseng Kwong Chi (whom Haring would supply with maps of the their locations upon returning to his studio), most went unrecorded, thus creating one of the most ephemeral epics in the history of the city.

The examples included in the exhibition can be regarded as relics of “an ever-changing exhibition available to the public 24 hours a day for the price of a token,” as curator Barry Blinderman wrote in 1990.4 Unsigned and undated, they are distinguished as much by Haring’s unmistakable hand as they are by the tireless body that guided it. In a preface for a 1985 exhibition catalog, artist/writer Brion Gysin referred to Haring’s broad, incisive line as “carved…like the one the man made when he first used it to cut what he wanted out of the air in the back of a cave.” 5 Haring never relied on preparatory sketches for his works on paper, canvas, or the dozens of murals he realized before his death due to AIDS-related complications in 1990. Films that document Haring making the chalk drawings, some of which were completed in only seconds, demonstrate the immediacy of his process. They reveal, for example, that he might begin rendering one of his humanoid figures at the very bottom of the subway panel, starting with a foot, and then proceed from there without breaking his line.

Installation view, "Keith Haring: Subway Drawings," 2011, Spruance Gallery, photo: Greenhouse Media

Encouraged by his father, who entertained Haring from an early age by sketching cartoon animals with him, the boy drew incessantly and eventually came to think of the activity as a “way of commanding respect and communicating with people”.6 By the time he was eighteen, Haring’s work had become more abstract, geometric, and focused on spontaneous gesture. Discouraged by two semesters at the Ivy School of Professional Art in Pittsburgh, at the age of twenty he moved to New York City to continue his education at the School of Visual Arts. Inspired by Eastern calligraphy, he started to experiment with painting on large sheets of paper, often videotaping the process and talking with passersby who stopped at the wide doors of his street-level studio on 22nd Street to watch him work. “This was the first time,” Haring wrote, “that I realized how many people could enjoy art if they were given the chance.” 7

The “commitment to drawing worthy of risk” was, for Haring, one of the many attributes of the work of graffiti artists gaining acceptance at the time.8 Not wanting to imitate their efforts and excited by the science of semiotics to which he had been recently introduced at SVA, Haring recognized the Manhattan Transit Authority as an ideal laboratory for engaging a diverse (non-art) audience. The MTA became a platform for experimenting with a cast of readily identifiable characters that were emerging in his drawings in 1980. Haring positioned these outlined figures, the “radiant child”, the “barking dog”, the “flying saucer”, among others visible in this exhibition, inside frames he drew along the perimeter of every black sheet. (A unifying trope of Haring’s work, this linear border could reference the TV screen, the proscenium, or a panel from a comic strip.) Thanks to the inexhaustible permutations of Haring’s flexible syntax, these figures assumed the identity of potent signs that could address a range of themes, both topical and universal, in a manner ideally suited to the viewing conditions of commuters. While occasionally riffing on adjacent advertisements, the drawings are devoid of allusions to any physical context save what we might discern as the abstract spaces of the subway itself. Rarely using any text (with the exception of marking the arrival of the new year or a invoking a call to “Free South Africa”, for example), it is Haring’s protagonists and their interactions that take our attention.

Manifesting a return to expressive figuration in the art world of the late 1970s (as well as in Haring’s own practice), the subway drawings also represented a conflation of studio and public space, cartoons and graffiti. Although Haring never identified himself as a graffiti artist, he was arrested many times for defacing public property. (Whatever damage he may have done was superficial and reversible and many of the police that handcuffed him became his fans.) The largest work in the exhibition, technically not a subway drawing, underscores the difference between graffiti and Haring’s singular enterprise. This plywood panel—with its wheat-pasted flyers and a sheet depicting “high risk groups” for AIDS—is as much a time capsule of the early 1980s as it is the record of inadvertent collaboration. Tagged with spray paint and magic marker, it includes a procession of Haring’s babies and dogs as well as multiple tags by SAMO (a.k.a. Jean-Michel Basquiat), whom Haring met and befriended in 1979. Hovering above the word “AARON” (an allusion to Henry Aaron), and the top of one of Basquiat’s boxy cars, is the signature three-pointed crown.

Untitled (computer head), ca. 1980 - 1983, chalk on black paper, 34.5” x 45”Collection of Larry Warsh, Keith Haring artwork © Keith Haring Foundation. Photo credit: Aaron Igler, Greenhouse Media.

We can now regard Haring’s subway drawings as a synthesis of performative process, automatic writing, and democratic access.9 Central to appreciating the evolution of his practice and its attempt to dissolve barriers between street culture, gallery work, and commerce (manifest most boldly by his Pop Shops), they remain pertinent to subsequent generations of artists, from the merchandise-savvy Takahashi Murakami to those such as FAILE, Banksy, Shepard Fairey, and Swoon, among many others working in the realm of “uncommissioned urban art”.10 While all of these efforts fuse idiosyncratic, graphic style with iconic characters using forms of prodigious public address, Haring’s subway drawings remain emblematic for their generosity, their celebration of unmediated, autographic mark-making, and their ability to invite and reward interpretation.

1 This show coincides with several relevant exhibitions featuring related material, including “Art in the Streets”, the first major U.S. museum exhibition of the history of graffiti and street art (to open April 17, 2011 at the Geffen Contemporary at MoCA, Los Angeles); “Keith Haring: 1978-82” (at the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, on view through September 5, 2011), and “Keith Haring”, a survey inaugurating the Gladstone Gallery’s representation of the Keith Haring estate that will open on May 4, 2011 (Haring’s birthday) and runs through July 1 of this year.

2 Untitled essay by the artist from Art in Transit, Subway Drawings by Keith Haring, (New York: Harmony Books, 1984). http://www.haring.com/cgi-bin/essays.cgi?essay_id=01

3 Remarks made by Oswald during “Notes from the Underground”, a panel discussion held on April 5, 2011, in Stiteler Auditorium, at Arcadia University in conjunction with the opening of this exhibition.

4 Barry Blinderman, “Close Encounters with The Third Mind”, catalog essay in Keith Haring: Future Primeval, (Normal, Illinois, Illinois State University, 1990) 18.

5 Brion Gysin, “The Sculpted Line,” introduction to Keith Haring, catalogue of the exhibition at CAPC, Musee d’Art Contemporain Bordeaux (Bordeaux: 1985), 9.

6 Untitled essay by the artist from Art in Transit, Subway Drawings by Keith Haring, (New York: Harmony Books, 1984).

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 The reference to “automatic writing ” was made by Carlo McCormick in a phone conversation with the author in late March, 2011.

10 Term used by Carlo McCormick during the aforementioned presentation at Arcadia (April 5, 2011) and used for the title of Trespass: A History of Uncommissioned Urban Art (Taschen, 2010) to which McCormick contributed an essay.

Thanks to Kermit Oswald, Carlo McCormick, and Larry Warsh for all the information they shared so generously as part of the realization of this exhibition. — Richard Torchia

Lecture

Notes From the Underground

Tuesday, April 5, 2011

KERMIT OSWALD, childhood friend of Haring and President of the Keith Haring Foundation from 1991-2009

CARLO McCORMICK, writer, independent curator, and senior editor of Paper magazine

Between 1980 and 1985, Keith Haring (1958-1990) produced thousands of chalk drawings on the black sheets of paper pasted over un-rented advertising panels in the New York City Subway. Executed in public at a rate of sometimes several dozen a day, these spontaneous images represented an energetic synthesis of performative process, universal iconography, and democratic display that was as unprecedented as it proved to be influential. This event features commentary by two individuals who witnessed this continuous succession of images first hand. Following their brief illustrated presentations, Oswald and McCormick will discuss the subway drawings in relation to the evolution of Haring’s practice and its legacy. The lecture will be held in Stiteler Auditorium, Murphy Hall at 7:30 PM.

A public reception will follow outside the gallery immediately afterwords. Both events are free and open to the public.