August 18 – November 1, 1998

Beaver College Art Gallery

“Amy Hauft: Period Room” is accompanied by an 82-page catalogue with essays by Patricia C. Phillips, Gregory Volk, and Connie Butler. For inquiries please contact gallery@arcadia.edu

New York based artist, Amy Hauft’s sculpture practice involves interventions into galleries, museums, and non-traditional sites that in the words of the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art Curator, Connie Butler, have contributed to “the dissolve of the category that is installation art.” Hauft’s pieces often employ expansive planes of light-porous materials (theatre netting, organza, tracing paper) applied elegantly but pragmatically in response to the architecture of a given site to provide viewers with a refreshing awareness of the body in contact with a specific setting.

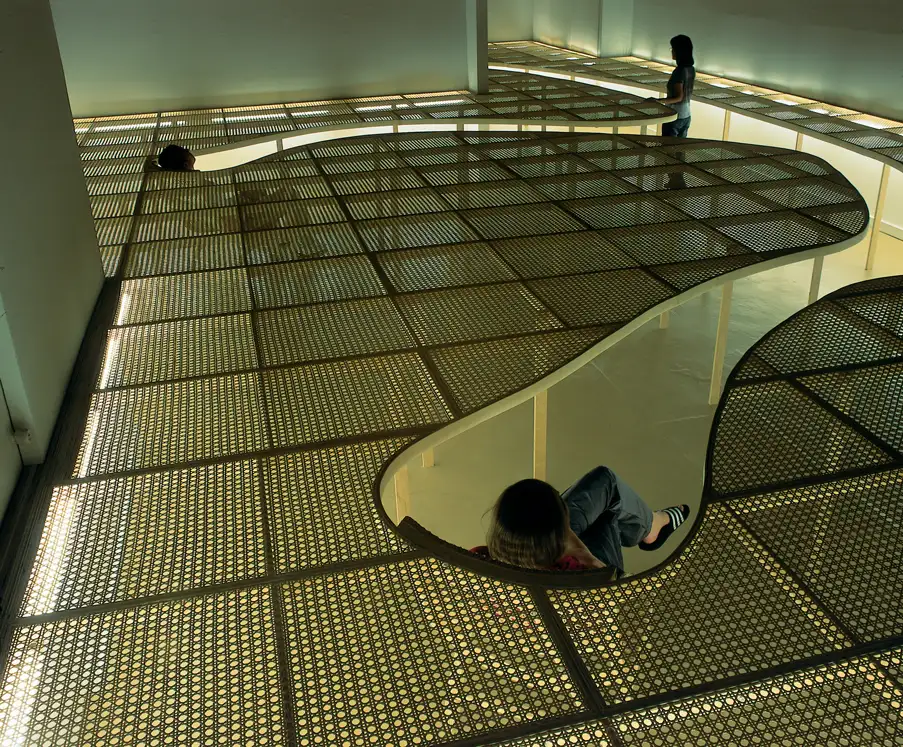

Installation view, “Period Room: A Project by Amy Hauft,” Beaver College Art Gallery, 1998

For her project at Beaver College Art Gallery, Hauft constructed a horizontal plane of caned plywood frames suspended at waist-level, wall-to-wall, throughout the 1200-square foot space. Three paths cut into this straw-colored, flood-like barrier led visitors to chaises designed and hand-caned by the artist. By integrating pathway, floor, and furniture at an exuberant scale, the installation both enveloped and supported the body, offering viewers the sensation of “wearing” space as if it were a garment. Lit from beneath by fluorescent fixtures and from above by natural light, the plane became transparent or opaque depending on the viewer’s position in the room.

Visitors were encouraged to recline in Hauft’s chairs, each of which offered ideal vantage points from which to view the 30-foot high, gabled ceiling and proto-modernist web of steel trusses that distinguish the 1893 structure that houses the gallery. Formerly a power station, the building was designed by Horace Trumbauer (1868-1938), a member of the team that drafted the plans for the Philadelphia Museum of Art (1911-28), whose many period rooms supply inspiration for Hauft’s project.

Hauft’s unprecedented application of caning—which we generally see in only discrete amounts of usually no more than one square foot at a time—is expanded from her installation at Beaver by the presentation of six historic cane chairs in area collections. These chairs were selected by the artist and designated at each venue by a free multiple—a printed cardboard disc that illustrated the chosen chair on one side and reproduced Hauft’s own hand caning on the other. Three of the chairs Hauft chose were determined as much for their sites as for the intrinsic beauty and history of the chairs. These venues included the second story Oval Parlor at Lemmon Hill (a federal mansion in Fairmount park), the Conservatory at Wyck (one of the oldest houses in Germantown), and the gallery at the Athenaeum of Philadelphia (a museum and library of decorative arts on Washington Square whose Reading Room is furnished with over 30 caned armchairs and stools).

The Heywood Brothers’ Recamier Settee (c. 1885-90) and Mies van der Rohe’s 1927 cantilever chair were presented on platforms at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in niches far from their original settings to provide viewers with a different perspective of the role these pieces play in the history of design. At the American Philosophical Society, one of a set of 34 popular chairs was placed in the lobby outside the Society’s famous library, which holds among other significant papers, all the historic records of Wyck.

Caning satisfies Hauft’s fascination for labor-intensive process and the deployment of spacious planes that restrain bodily passages yet can be seen through. Caning is also a potent cultural form rich in world history. A caned day-bed, for example, was among the treasures found in Tutankhamen’s tomb, although it is Indian craftsmen who are credited for developing the use of woven rattan reeds for the seats and backs of chairs. More resilient and durable than European alternatives, caned chairs were portable and ideal for use in warm weather. Despite their lightness and comfort, however, they were initially frowned upon because of their cheapness. Demonstrating an example of upward social mobility in furniture, caned chairs eventually found their way into the grandest and most splendid interiors of England. It was during the 1890s (during the construction of the power station that now houses the gallery) that the rage for caned seats in the United States reached its peak—a fashion imported from Great Britain prompted by interest in Oriental products. A century earlier, Philadelphia was the primary American port for receiving rolled cane from China—a form of mass-produced, pre-fabricated caning still in demand today and which Hauft matches deftly with her own hand-woven cane work. Her unique approach to craft embraces these and other historical references to create the compelling experience offered by her installation and the cultural matrix provided by the project as a whole.