February 1–April 15, 2018

Arcadia University Art Gallery

Arcadia University Art Gallery is pleased to present “Richard Mosse: Beyond Here Lies Nothin’” an exhibition by Irish conceptual photographer Richard Mosse (b. 1980) based in New York.

Installation view (left to right), Here Come The Warm Jets, North Kivu, Eastern Congo (2012), Vintage Violence (2011), The Crystal World (2011) photo: Sam Fritch

The show presents examples from two recent projects, one examining the current refugee crisis in Europe (Heat Maps [2016-ongoing] and Incoming [2014-2017]) and the other recording the armed conflict in eastern Congo (Infra [2010-15]). Both bodies of work explore Mosse’s radical repurposing of military reconnaissance equipment to challenge the conventions of photojournalism and documentary filmmaking. Formally alluring yet freighted with ethical and political implications, images from both bodies of work elicit the complicity and empathy of viewers while proposing unforeseen ways of regarding these humanitarian disasters.

The exhibition represents Heat Maps with two panoramic prints depicting encampments in Lebanon and Liguria (northern Italy). These large-scale works, each ten feet wide, are accompanied by a selection of framed stills from a related 3-channel, 52-minute video installation, Incoming, realized in collaboration with cinematographer Trevor Tweeten and composer Ben Frost. Both the photographs and video installation were made with an extreme telephoto, military-grade thermographic camera that registers heat as opposed to visible light. Recently developed for long-range border enforcement, the 55-pound apparatus is classified as a weapon under international law. Difficult to transport and cumbersome to operate, its tunnel-vision optics can penetrate smoke and atmospheric haze to detect warmth radiating from a human body as far as 18 miles away, day or night. Turning the rationale of this state-of–the-art technology against itself, yet alert to its expressive and formal possibilities, Mosse co-opts this military surveillance equipment to portray refugees escaping Northern Africa and the Middle East and settling in camps at the borders of Europe. The resulting images reveal a world translated into an incandescent, monochrome tonality that registers subtle differences in temperature but is completely blind to color. Captured by this equipment, Mosse’s figures are abstracted to biological heat signatures at the same time they are ennobled as members of the human species.

The two topographic views included in the exhibition were made by attaching the thermal camera to a robotic motion control tripod, thus allowing Mosse to scan the camps from elevated viewpoints required by the technology. Each panorama is built from hundreds of smaller exposures, each with its own vanishing point. These images are dense with details that articulate fence architecture, security gates, and temporary shelters at the margins of more developed urban areas. Closer inspection, however, reveals a wealth of incidental tableaux, individuals or groupings that evoke figures depicted in paintings by Bosch or Breughel. Mosse says that his approach allows “the viewer to meditate on the profoundly difficult and frequently tragic journeys of refugees through the metaphors of hypothermia, global warming, border enforcement, mortality, and what the philosopher Giorgio Agamben has called the ‘base life’ of stateless people.”

Hombo Walikale (2012), digital c-print on metallic paper, 40 x 87 1/2 inches, © Richard Mosse

Complementing the detached, topographical views of the two camps, six stills from Incoming provide more intimate access to refugees, as well as servicemen, soldiers, and pilots, thus confounding the narrative. One print, for example, clearly delineates figures on a lifeboat whose individual identities as refugees, immigrants, natives, or citizens remain obscure. This and other views from the series expose levels of human defenselessness that become universal and—in the words of Lucy Kumara Moore (writing in the December 2017 issue of Artforum)—challenge “the idea that we only empathize ‘usefully’ when we encounter the emotional recitations or visual traces of consenting individuals, which in the case of traditional photo documentary is somehow assumed to be ‘truthful.’”

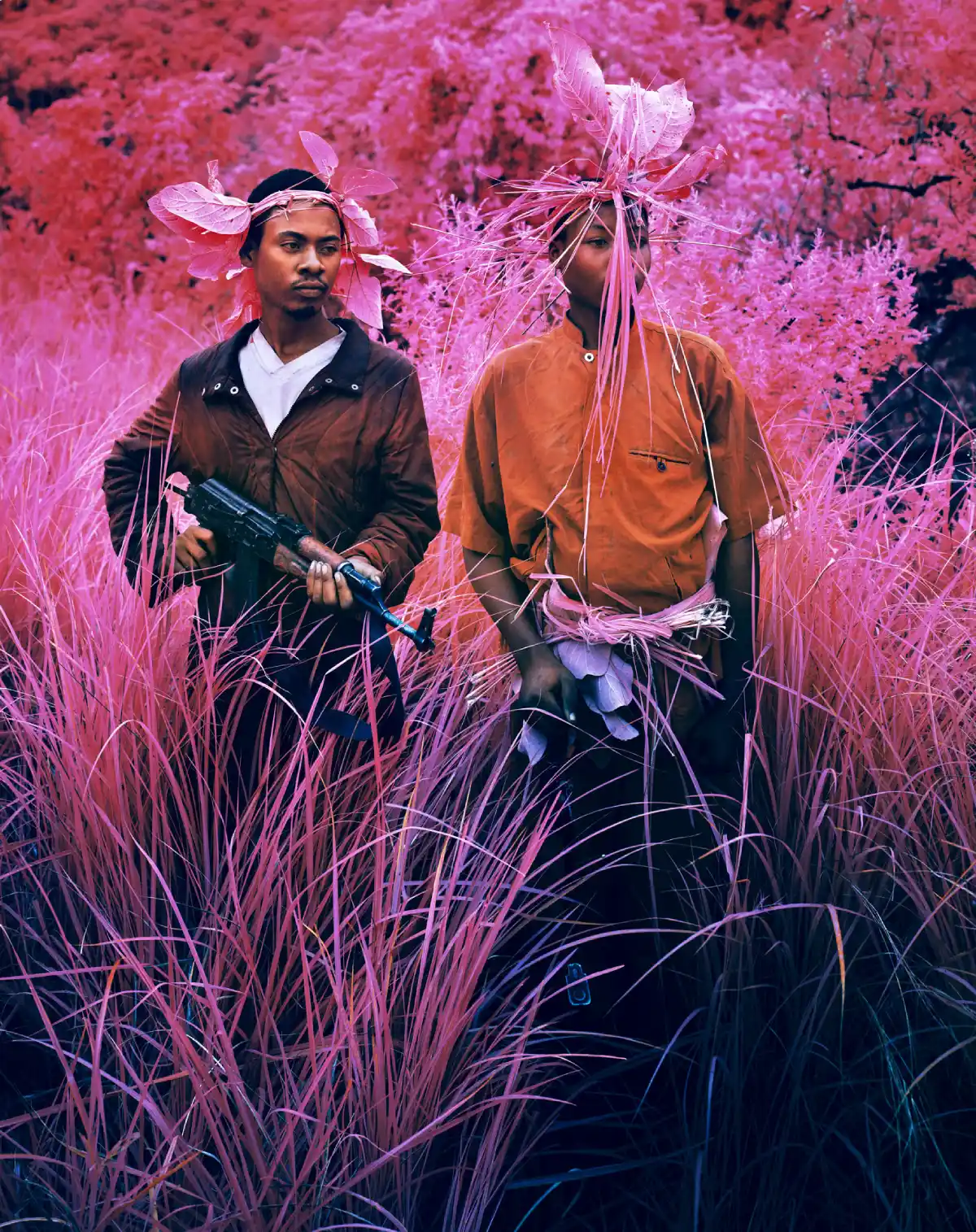

The question of the consenting subject plays a critical role in two photographs from Infra that depict armed rebels posing and‚ in the case of Vintage Violence (2011), staring directly into the lens. This uncanny combination of menace and the vulnerability is as striking as the unorthodox palette that distinguishes these color photographs. Begun in 2010, Infra documents the ongoing confrontation between the Congolese Army and remote rebel groups in eastern Congo whose constantly shifting allegiances have rendered this conflict nearly invisible despite the highest death toll since World War II. (Over 5.4 million people perished between the outbreak of the fighting in 1998 through 2008, yet the war remains woefully under-reported.)

Mosse recorded the struggle with a large format camera loaded with Kodak Aerochrome, a color infrared film that registers wavelengths of light reflected from chlorophyll (and invisible to the human eye) as shades of pink, red, and violet. Soldiers’ uniforms and equatorial foliage become lavender, crimson, and fuschia. Developed in the 1940s at the onset of the Cold War in collaboration with the U.S. military and discontinued in 2009, the film was originally intended for aerial vegetation surveys to detect camouflaged targets. Mosse’s application of the stock to record a vicious conflict that has defied description not only exercises tropes of seeing vs. knowing, but also interprets Congo’s historic bounty of natural resources as a candy-colored treasure. Infra thus recuperates an analog medium long considered dated—if not taboo for documentary purposes—due to the psychedelic (“soul-revealing”) effects it yielded for the covers of albums by Jimi Hendrix, the Grateful Dead, Donovan, and others from the late 1960s. Mosse explicitly references these associations with the carefully chosen titles of many of the prints from the series, including Frank Zappa’s Hot Rats.

Hot Rats (2012), digital c-print on metallic paper 50 x 40 inches, © Richard Mosse

In a recent interview about Infra with The British Journal of Photography, Mosse stated, “I wanted to export this technology to a harder situation, to up-end the generic conventions of calcified mass-media narratives and challenge the way we’re allowed to represent this forgotten conflict…I wanted to confront this military reconnaissance technology, to use it reflexively in order to question the ways in which war photography is constructed.”

Referring to his use of the Bob Dylan song to title the exhibition, Mosse explains: “It is said to have come from Ovid’s poems about exile, so relates to the themes of human displacement in both Infra and the Heat Maps. Plus, the song is about love, how we really have nothing if we lack love, and so there is nothing beyond love. It’s an important message in times of hate, wall building, and cultural war.”

Artist Lecture

February 28, 2018

Mosse will lecture about the work in the exhibition at 6:30 PM in the Mirror Room of Grey Towers Castle. A reception will follow immediately afterward in the Gallery. Both events are free and open to the public.

ABOUT RICHARD MOSSE

Richard Mosse is a recipient of the 2017 Prix Pitcet Award, the Deutsche Boerse Photography Prize, the Yale Poynter Fellowship in Journalism, the B3 Award at the Frankfurt Biennial, a Guggenheim Fellowship, a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, and the Leonore Annenberg Fellowship. In 2015, he was named a nominee member of Magnum Photos. Incoming premiered at the Barbican in London in 2016 and was included in the National Gallery of Victoria Triennial. His immersive, six-channel 16mm infrared film installation, The Enclave, made in conjunction with Infra, was exhibited at the National Pavilion of Ireland during the 55th Venice Art Biennale. Mosse has also exhibited in solo and group exhibitions internationally at venues such as Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk; FOAM, Amsterdam; Portland Art Museum, Oregon; National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne; The Nasher Museum, North Carolina; Reykjavik Art Museum; Irish Museum of Modern Art; Akademie der Kunste, Berlin; MIT Boston; Lille3000; Kunsthaus Graz; MCA Chicago, and others.