Arcadia University Art Gallery Presents

Tables of Contents: Ray Johnson Bob Box Archive

September 6 – October 16

About the Exhibition

Arcadia University Art Gallery is pleased to announce the opening of “Tables of Contents: Ray Johnson Bob Box Archive”, an exhibition exploring the seven-year exchange between the legendary late artist Ray Johnson and college-artist Robert Warner. Featuring the contents of 13 cardboard boxes given to Warner by Johnson in 1990, the exhibition also includes a sampling of the two artists’ correspondence and a selection of finished collages from the Ray Johnson Estate. Initially presented at Esopus Space (New York City) in June 2011, the exhibition coincided with the latest issue of Esopus Magazine, which featured a generously illustrated 16-page spread about the archive.

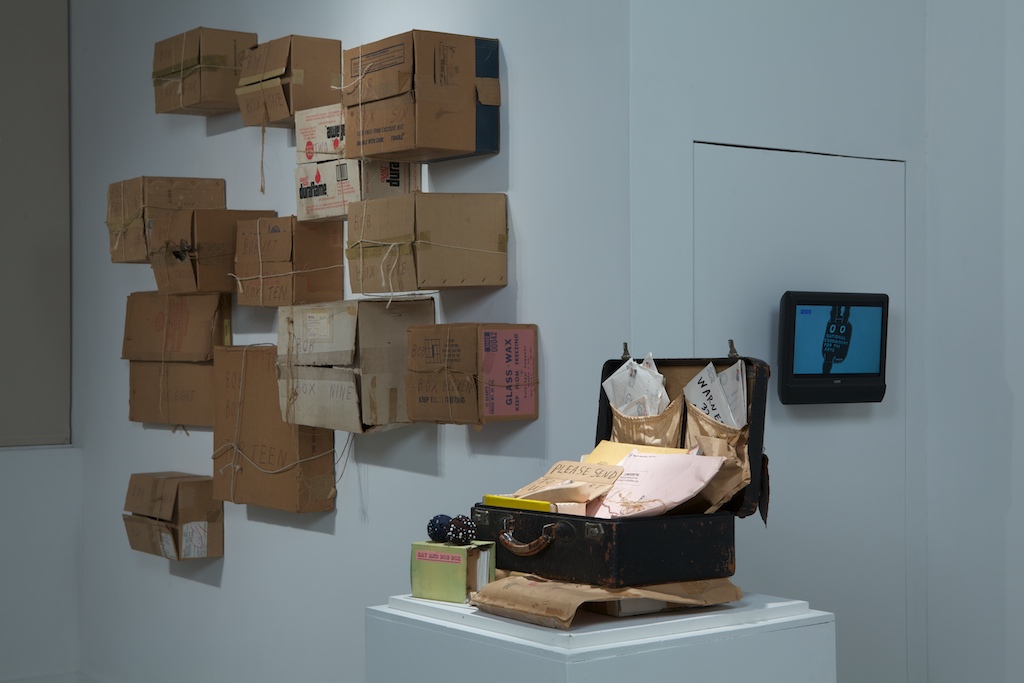

Installation view, "Tables of Contents: Ray Johnson Bob Box Archive," 2011, Spruance Gallery, photo: Arcadia Exhibitions

The show has been re-titled for its presentation at Arcadia to reflect the gallery’s comprehensive display of the contents of all 13 cardboard boxes. Offering viewers unusual entrée to the archive, this approach strives to echo the extensive series of events at Esopus Space during which Warner opened each of the boxes in public, discussed its contents, and selected certain examples to mount on the gallery walls.

At Arcadia, the hundreds of found objects, many discovered on the beach near Johnson’s Long Island home in Locust Valley, New York, are arranged on tables sourced from the campus. This sundry assortment of items, which at first seems too varied to categorize, is joined by other objects and printed matter sent or bequeathed to Johnson by other correspondents. Despite the confounding variety of material, precise themes begin to materialize. These graphic coincidences and plays on words, names, and subjects (including a motley cast of art world and Hollywood celebrities) are gently underscored by five exquisite collages dating from 1972 to 1981.

Warner, an optician working in New York City, first encountered Johnson’s work on a postcard sent to a mutual friend in 1988. Intrigued by the possibilities of corresponding with an artist, Warner initiated what evolved into a intense exchange between the two that continued until Johnson’s death in 1995. While they spoke on the phone nearly every day, they met in person only seven times. (Obsessively private, and rarely attending his own exhibition openings, Johnson discouraged visits to his home in Long Island, where he relocated from Manhattan in response to being threatened by an attacker with a knife on the subway the same day that Andy Warhol was shot in 1968.)

Installation view, "Tables of Contents: Ray Johnson Bob Box Archive," 2011, Spruance Gallery, photo: Arcadia Exhibitions

At one point in 1990, Warner informed Johnson that he was going to be at garage sale in Great Neck, New York. As Warner tells the story in the Esopus 16 interview: “Ray called and asked me if I was going to have transportation back to the city, and I told him I would. He pulled up in front of the house in his Volkswagen. He was very cordial and shook hands with everyone, and then he said to my friend’s husband, who was driving me back, ‘Can I put these things I brought Bob in your trunk?’ And I said, ‘What things?’ He proceeded to take out of the car 13 cardboard boxes tied with twine, labeled ‘Bob Box 1,’ ‘Bob Box 2,’ ‘Bob Box 3’….”

The cardboard boxes, temporarily relieved of their contents and still wrapped in the string that Warner has never untied, are also on display in the gallery. The set of thirteen is not unlike other boxes of documents and objects that Johnson offered (either en masse or one at time) to friends and correspondents over the years, including Fluxus artists Alison Knowles and Dick Higgins. The identity of these cartons as gifts distinguishes them from Andy Warhol’s 612 cardboard “Time Capsules”—filled from 1974 to Warhol’s death in 1987—with which they nevertheless have an affinity. (In considering Johnson’s boxes, it might be useful to remember that the artist frequently used cardboard cartons to transport his finished collages to meetings with collectors—sometimes scheduled in hotel rooms—during which he would unpack the works he’d selected and display them on available furniture.) Johnson was not insensitive to the impact these offeringshad on his friends. Worried that the contents of the five large boxes he gave to poet Coco Gordon were making her anxious, Johnson told her to “just throw it all out into the water”. Tellingly, when police entered Johnson’s house following his drowning suicide, they found it filled with neatly stacked cardboard containers.

Among the affecting dimensions of this exhibition is the precarious status of the items the Bob Boxes have housed for so long. Writing in The New York Times about the show’s original incarnation at Esopus Space, art critic Holland Cotter mentions the unspoken understanding that Warner would take care of the containers. (In the space of only two years, Johnson had come to know the optician as a responsible and dedicated correspondent.) Viewers studying the archive as presented in the gallery may begin to sense for themselves the “custodial duties” originally bestowed by Johnson to Warner. In this way, they might experience a variation of the “collaboration and physical inconsequentiality” on which Cotter claimed much of Johnson’s work was based. Ultimately we are left with both the challenge and the pleasure of reading the archive as an open but mysterious landscape of clues to the fascinating world Johnson made for himself and the way he shared that world with others.

Instllation view, detail, "Tables of Contents: Ray Johnson Bob Box Archive," 2011, Spruance Gallery, photo: Arcadia Exhibitions

Event in conjunction with Tables of Contents: Ray Johnson Bob Box Archive

OPENING EVENT

Tuesday, Sept. 13, 6:30 PM, Little Theatre, Spruance Art Center

Conversation between Robert Warner and Tod Lippy, Editor, Esopus Magazine. Followed by a reception in the art gallery. Free and open to the public.

GLENSIDE CORRESPONDENCE SCHOOL

Saturday, Oct. 1, 2-5 PM, Art Gallery

An afternoon with Robert Warner and company. Free and open to the public.

Join artist and exhibition curator Robert Warner in a variety of activities pertaining to “Tables of Contents”. In addition to offering an informal tour of the show, Warner will demonstrate processes pertaining to his correspondence with Johnson, including the creation of silhouette portraits and the use of rubber stamps. Employing a light box, Warner will explore—for the first time—an archive of carbon paper (c. 1950 – 1990) that Johnson used to copy typed letters and drawings. To address the influence of Joseph Cornell on Johnson’s practice, the afternoon will include a conversation with artist Howard Hussey, studio assistant to Cornell from 1966 to 1972. More details and a schedule of activities to be announced.

About Robert Warner

Born in Geneva, New York, in 1956, Robert Warner is a collage artist, letterpress printer, optician, and eyewear designer who currently resides in Greenwich Village, New York City. Untrained as an artist, Warner’s seven-year correspondence with Ray Johnson, begun in 1988, encouraged him to take up collage and initiated his interest in hand-set type, letterpress printing, and the production of custom, handcrafted display boxes. From 1995 to 2010 he worked as a job printer for Bowne & Co. Stationers at the Seaport Museum (New York City) where, using historic presses, plates, and equipment, he produced stationery and commemorative items to help raise funds for the institution. His collages, which incorporate vintage images and papers, have been exhibited at the New York Public Library, Pavel Zoubok Gallery, and the Center for Book Arts, all in New York City.

About Tod Lippy

Tod Lippy is the editor and founder of Esopus, a twice-yearly arts magazine esteemed for its unmediated perspectives on contemporary culture from a wide range of creative professionals. Referred to by The Atlantic Monthly this past April as “the best magazine you never heard of”, it includes artists’ projects, critical writing, fiction, poetry, visual essays, interviews, and, in each issue, an audio CD. Published by the non-profit Esopus Foundation Ltd., the magazine, which is entirely free of advertising, has a mission “to provide an unfiltered, non-commercial space in which creative people and the public can connect in meaningful, productive ways.” In addition to being president of the Esopus Foundation Ltd., Lippy also runs Esopus Space, an alternative exhibition and performance venue that began presenting public exhibitions in 2009. Lippy was the editor and co-founder of Scenario: The Magazine of Screenwriting Art (1994–97), the publisher and co-editor of publicsfear magazine (1992–94), and a senior editor at Print magazine from 1990–1997. His 2000 book,Projections 11: New York Film-Makers on Film-Making, was published by Faber & Faber. Lippy’s 1999 short film, Cookies, was featured in over 20 film festivals in the U.S. and abroad.

Lippy has lectured on Esopus at many educational and cultural institutions, including the American Library Association, the American Institute for Graphic Arts, the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, the School of Visual Arts M.F.A. Design Program, Hunter College’s M.F.A. Program; the Fashion Institute of Technology, Rice University, USC’s Roski School of Fine Arts, New York’s Nightingale-Bamford School for Girls, and the Elizabeth Irwin High School. He has been interviewed on the same subject for a number of journals, websites, radio programs, and books, including Becoming a Graphic Designer (Wiley, 2005) and Fresh Dialogue: Making Magazines (Princeton Architectural Press, 2007).