February 25–April 25, 2016

Arcadia University Art Gallery

Arcadia University Art Gallery announced the opening of “Pati Hill: Photocopier—A Survey of Prints and Books (1974-83)”, on view from Feb. 25 to April 24, 2016.

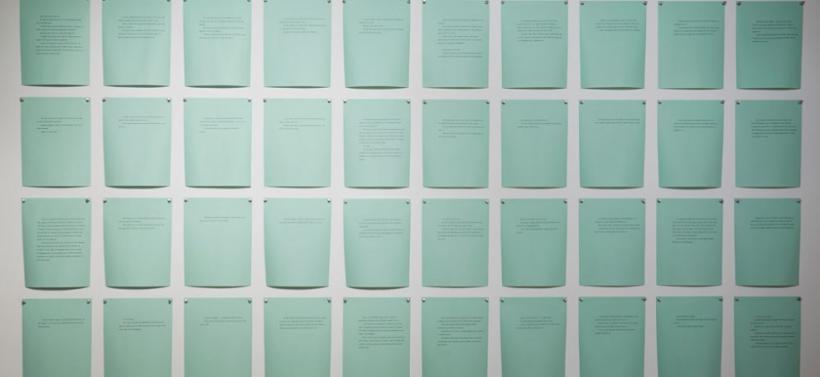

View from the entrance of Arcadia University Art Gallery, Spruance Fine Arts Center. Photos: Greenhouse Media

View from the entrance of Arcadia University Art Gallery, Spruance Fine Arts Center. Photos: Greenhouse Media

View of A Swan: An Opera in Nine Chapters installation room, Arcadia University Art Gallery, Spruance Fine Arts Center. Photos: Greenhouse Media

View of Great Room Lobby Gallery, University Commons, lower level. Photos: Greenhouse Media

View of Commons Art Gallery, University Commons, upper level. Photos: Greenhouse Media

View of Dreams Objects Moments, Commons Art Gallery, University Commons, upper level Photos: Greenhouse Media

View of Commons Art Gallery, University Commons, upper level. Photos: Greenhouse Media

View from the entrance of Arcadia University Art Gallery, Spruance Fine Arts Center. Photos: Greenhouse Media

View from the entrance of Arcadia University Art Gallery, Spruance Fine Arts Center. Photos: Greenhouse Media

View of A Swan: An Opera in Nine Chapters installation room, Arcadia University Art Gallery, Spruance Fine Arts Center. Photos: Greenhouse Media

View of Great Room Lobby Gallery, University Commons, lower level. Photos: Greenhouse Media

View of Commons Art Gallery, University Commons, upper level. Photos: Greenhouse Media

View of Dreams Objects Moments, Commons Art Gallery, University Commons, upper level Photos: Greenhouse Media

View of Commons Art Gallery, University Commons, upper level. Photos: Greenhouse Media

Employing the machine to scan items as common as a gum wrapper or as unexpected as a dead swan, she also used the copier to transform appropriated photographs. Hill published and exhibited her copier prints, often alongside her own texts, some of which addressed her application of the machine with an uncanny wit. Featuring over one hundred prints, the exhibition examines the initial stages of Hill’s decades-long exploration of the medium and its facility at combining image and text.

Michelle Cotton, Director, Bonner Kunstverien (Bonn, Germany)

Born in 1921, Hill was a published author before she started to explore the copier at the age of 53 at a moment of promise for an evolving technology that is almost invisible to us now. She was not alone in experimenting with xerography. However, her approach to the medium, coupled with her inspired writing about it, proved singular and prescient, especially regarding its potential for self-publishing and image-sharing. Unlike many artists who flirted with this instant-duplication process—a medium whose affordability and use of plain paper made it revolutionary—Hill sustained her commitment to xerography (or “dry writing,” from the Greek) for forty years, never wavering from her aspiration to create works in which image and text might “fuse to become something other than either.” In a 1980 profile in The New Yorker, Hill remarked: “Copiers bring artists and writers together. Copies are an international visual language, which talks to people in Los Angeles and people in Prague the same way. Making copies is very near to speaking”.

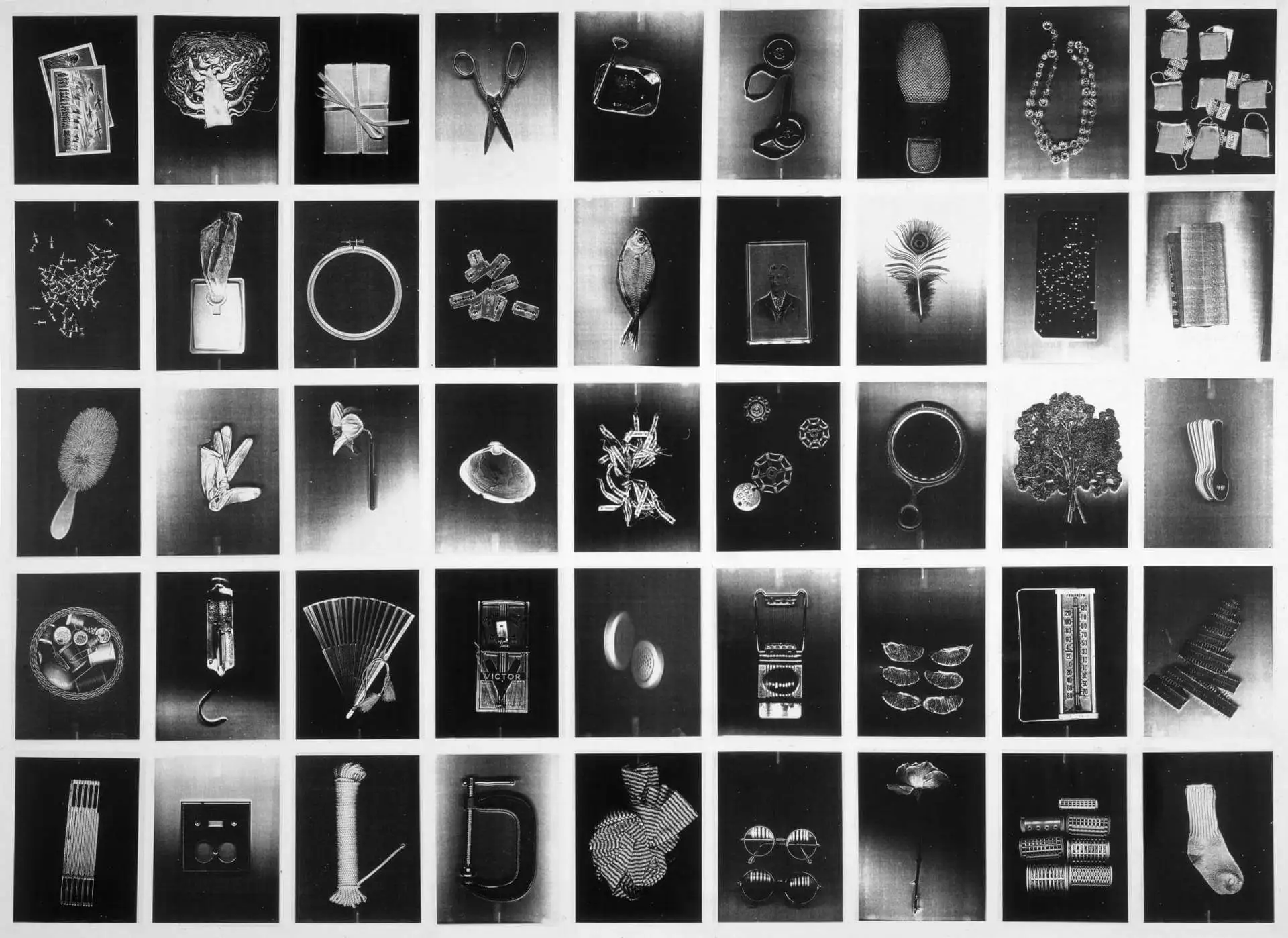

The exhibition begins in the Spruance Art Center with a sampling of Hill’s earliest prints made at a local copy shop near her home in Stonington, Connecticut, when Hill was emerging from a 12-year hiatus from publishing. These small works—scans of domestic items printed at life scale and cropped to sizes sometimes no larger than a single button—eventually became illustrations for Slave Days (1975), Hill’s second book of poems that alludes to her identity as a housewife and mother.

The objects Hill chose to copy, which she could not fully ascertain until the machine had seen them, are visually transformed yet faithfully convey their intrinsic properties, as well as those of the copier. “It repeats my words perfectly as many times as I ask it to,” Hill wrote, “but when I show it a hair curler, it hands me back a space ship, and when I show it the inside of a straw hat it describes the eerie joys of a descent into a volcano.”

The show explores Hill’s appreciation of what she called the “distancing” effects of IBM’s Copier II, a machine whose rich blacks made the objects she chose, when scanned with the lid up, appear to be “lit by lightning” and suspended in a vacuum. During the first years of her experimentation, Hill employed this IBM model almost exclusively, often loading the machine with extra toner to achieve the velvety black backgrounds that distinguish her prints. Thanks to a chance encounter on a transatlantic flight from Paris to New York with designer Charles Eames, IBM loaned Hill one of these machines and installed it in her Connecticut home. Several bodies of work made on this model are included in the exhibition, most of which were exhibited at the Kornblee Gallery (New York) in solo exhibitions between 1975 and 1979. Excerpts of these projects were also published in her book Letters to Jill: a catalogue and some notes on copying (1979), which serves as a primary resource for the exhibition as well as jargon-free primer on the medium.

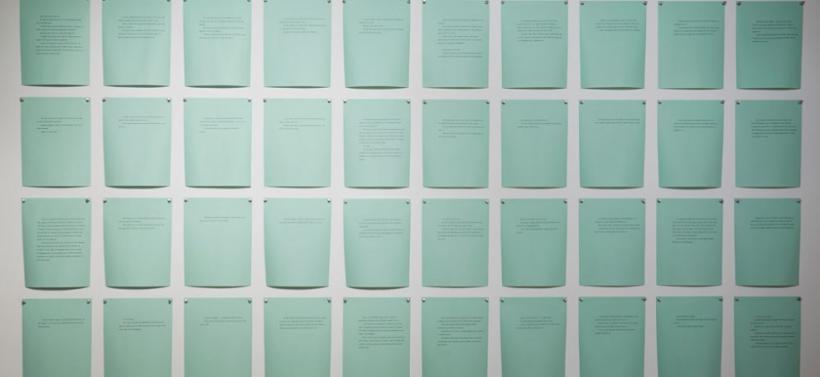

Installation of Alphabet of Common Objects

Hill’s ongoing preoccupation with universal signage—including a hieroglyphic language that she devised and taught to children (also featured in the exhibition)—informs her Alphabet of Common Objects (1977-79). This grid of 45 scans of everyday household items (an egg slicer, a glove, a sprig of parsley, etc.) isolated in the center of a letter-sized sheet, can be read as an array of symbols, each as generic as it is subjective, as is demonstrated by a selection of short texts she wrote for some of them.

Hill’s search for a perfect white feather—the flatness and detail of which Hill claimed made it an ideal subject for the copier—led her to A Swan: An Opera in Nine Chapters (1978). This installation of 32 captioned prints transforms the body of a dead bird she found on the Stonington beach into a mythic tale and remains her most dramatic experiment on the magnifying impact of words on pictures and vice versa. The project has not been seen in the United States since 1980 when it appeared in the traveling exhibition “Electroworks” at the Cooper Hewitt Museum, the first major survey of the medium organized by the George Eastman House, Rochester, New York.

Installation view, Arcadia University Art Gallery, photo: Greenhouse Media

Unlike most other artists who used the copier to create collages or alter existing images, Hill used the machine in a literal way, having come to “copying from writing” as she stated. She admitted to letting the copier “dominate” her work and much of her experiments can be regarded as an ongoing investigation into the limits and the possibilities of the medium. Many of the prints she made between 1974 and 1983 represent a dialogue she conducted with this highly responsive and immediate process. Her fascination with how the machine “saw” or interpreted physical objects extended to pre-existing images as well. Her illustrated novel Impossible Dreams (1976) and the series that comprise Men and Women in Sleeping Cars (1979) demonstrate Hill’s use of the copier to unify images from diverse sources while underscoring their narrative implications. Impossible Dreams is presented in the Arcadia exhibition by an audiotape of Hill reading the novel (accompanied by projected slides) at Hallwalls (Buffalo, New York) in 1979.

Two bodies of work from the early 1980s are also featured in two galleries housed in the adjacent University Commons – marking the first time that all three of these venues will be used to stage a single exhibition at Arcadia. Hill’s copier prints of a single scarf, which she renders as a lexicon of infinitely malleable forms, extend her concerns with language and signs. The show concludes with a look at her first attempts to “copy Versailles”. These forays include scans of materials gathered from the palace and grounds, including found objects, tufts of grass, cobblestones, and an espaliered pear tree, which she was able to transport to her studio and scan one small section at time. Hill never exhibited these initial black and white prints as individual works, choosing instead to re-copy them, often with colored toner. These she eventually arranged in large, tiled grids or single composite images that she continued to develop into the late 1990s, sometimes as etchings. The exhibition concludes with a sampling of the original prints.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a publication and series of public programs. The first of these, a lecture by exhibition curator and gallery director Richard Torchia, will open the exhibition on the evening of February 25. Entitled “Key Operator: An Introduction to the Work of Pati Hill”, it will begin at 6:30 PM in the Great Room of the University Commons. A reception, free and open to the public, will follow at 7:30 PM.

For more information, including hours and directions, visit http://gallery.arcadia.edu

The Benton Spruance Art Center is open Monday through Sunday, and the Commons Gallery is open all week. Hours and directions are available online at gallery.arcadia.edu.

Both locations are on Arcadia’s campus, at 450 S. Easton Road in Glenside.

Arthur Lublow, Author, “Diane Arbus: Portrait of a Photographer”

About Pati Hill

Pati Hill (1921-2014) was born in Ashland, Kentucky in 1921 and raised in Virginia by her divorced mother. Demonstrating an interest in writing and art from an early age, she took courses for a year at George Washington University before moving to New York in 1940 where she became a fashion model. While employed by the John Robert Powers Agency, she began writing articles and short stories for Seventeen and Mademoiselle. In 1941, Hill met photographer Diane Arbus, and the two remained close friends for the next three decades. (Hill dedicated her 1960 novel, One Thing I Know, to the photographer and translated Arbus’s introductory notes for the French edition of 1972 Aperture monograph.)

In 1947 Hill relocated to Paris to model the first American collection for couturier Molyneux. By the early 1950s, however, in an effort to concentrate on her writing, she moved to a derelict cottage in the French countryside in Montacher, Yonne, where she completed her first two books. The first of these to be published, The Pit and The Century Plant (1955, Harper’s and Brothers) was a memoir about her time at the cottage. The second, a The Nine Mile Circle (1957, Houghton Mifflin), was a novel that Hill told Arbus was about “a child who killed its fantasy self for sake of a friend.” Both were well received by critics who celebrated Hill’s powers of observation and originality of expression. (The novel was favorably compared to the work of William Faulkner.) With the encouragement of George Plimpton, she began publishing her short stories in The Paris Review, for which she also conducted an interview with Truman Capote in 1957 after she had returned to the United States and took up residence in New York City and Stonington, Connecticut.

In 1959, Hill met publisher and art dealer Paul Bianchini, whom she married in 1960. (Bianchini’s New York gallery, was one of the first commercial venues to exhibit Pop art.) In 1962, Hill gave birth to her daughter and published her first book of poems, The Snow Rabbit, illustrated by poet Galway Kinnell. Despite multiple residencies at MacDowell and Yaddo into early the early 70s, Hill did not publish again until 1975 when Slave Days, her first book to include images of her copier prints, was published with the assistance of her Stonington neighbor, poet James Merrill. New York gallerist Jill Kornblee gave Hill five solo exhibitions at her 57th Street Gallery between 1975 and 1979. One of these, “Garments”, was completed with inadvertent assistance from IBM thanks to weekend access to the company’s copiers at its New York offices provided by a supportive friend who worked there.

The following year, Hill was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts Creative Arts Fellowship for her illustrated novel Impossible Dreams. Additional sanctioned support for Hill’s work from IBM eventually came in 1977 as a two-and-a-half-year loan of one of its “Copier II” models thanks to the influence of designer Charles Eames. At the conclusion of the loan, Hill returned to Paris where she spent five years photocopying the details of the palace and grounds of Versailles, eventually presenting the resulting large-scale composite works on the site as well as other venues in France. In 1989 Hill and Bianchini opened Galerie Toner in Sens, a small town 75 miles southeast of Paris, where Hill had settled a few years prior. This gallery, like its Parisian counterpart, which opened in 1992, was dedicated to exhibiting work produced with copiers. Hill continued to publish books in small editions, show her work, and organize exhibitions until 2012.

Venues that have exhibited Hill’s copier prints include the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, Franklin Furnace (in New York City); the Centre Georges Pompidou, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, and the Cabinet des Estampes de la Bibliothèque Nationale de France (in Paris); Musée Lambinet (in Versailles); L’Orangerie des Musées de Sens, France; Gallery Modena, Bologne, Italy; and the Stedelijk, Museum, Amsterdam. Her artwork is included in the permanent collections of Bayly Art Museum (Fralin Museum), University of Virginia; the Bibliothèque Nationale de France; and L’Orangerie des Musées de France.

Major support for Pati Hill: Photocopier has been provided by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage. Additional assistance has been contributed by the Estate of Pati Hill, the Friends of Arcadia University Art Gallery, and Dorothy Lichtenstein

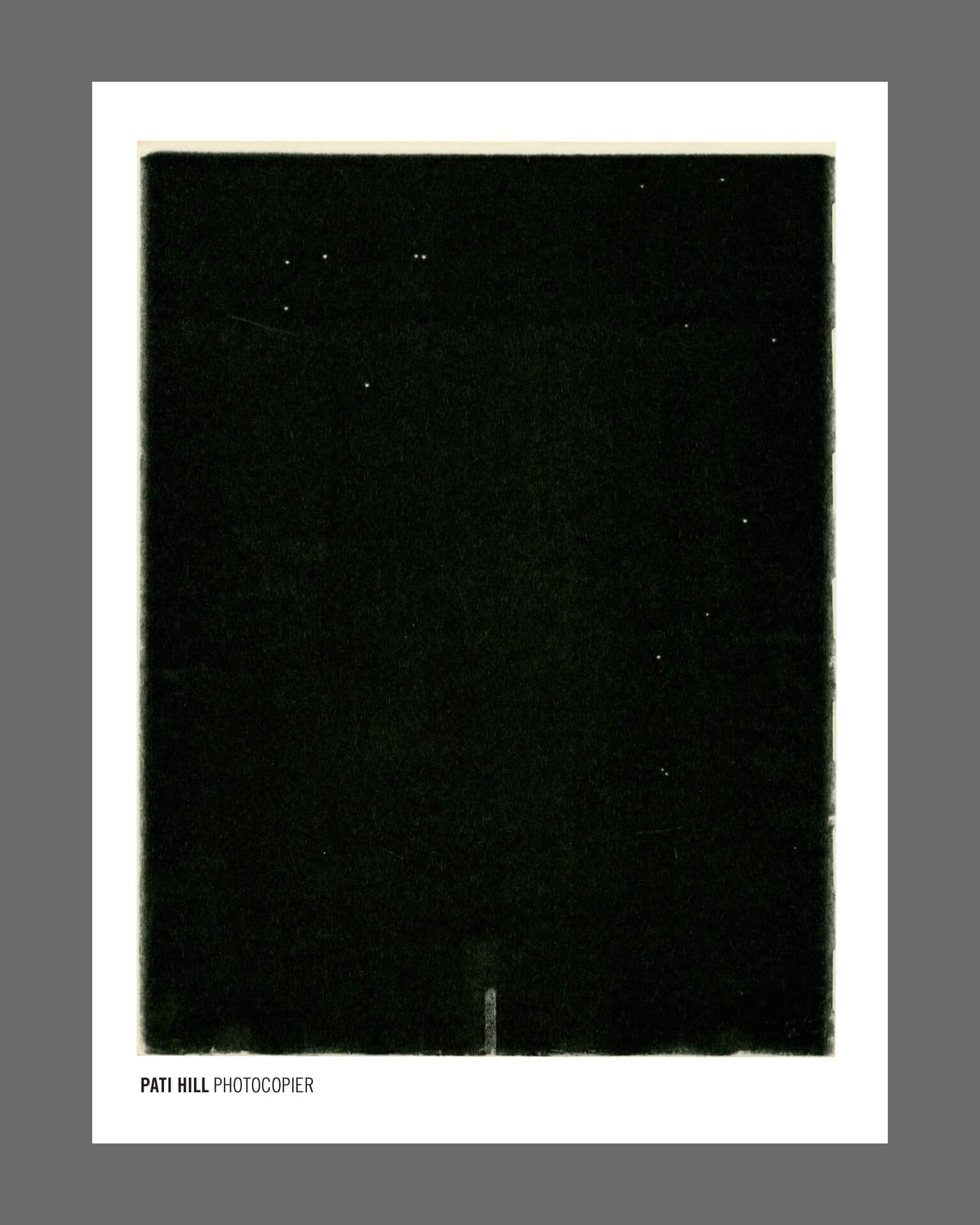

Pati HIll: Photocopier – A Survey of Books and Prints (1974-83)

200 pages

13″ x 10″

$30.00

The exhibition catalog is now available for purchase. Please direct all inquiries to gallery@arcadia.edu.