Feb. 25 to April 24: Arcadia University Art Gallery Presents ‘Pati Hill: Photocopier’

Arcadia University Art Gallery is pleased to present Pati Hill: Photocopier, A Survey of Prints and Books (1974–83). Featuring more than 100 works on paper depicting subjects as common as a gum wrapper and as expansive as the Palace of Versailles, this exhibition reconsiders the hybrid practice of Pati Hill (1921–2014). Untrained as an artist, Hill was a published novelist and poet before she started to explore the copier at age 53 at a moment of promise for an evolving technology that is almost invisible to us now. Hill was not alone in experimenting with what she called “a found instrument, a saxophone without directions.” However, her approach to the machine, coupled with her lucid writing about it, proved singular and prescient, especially regarding its potential for self-publishing and image-sharing that we take for granted today.

Unlike many artists who flirted with this instant-duplication process—a medium whose affordability and use of plain paper made it revolutionary—Hill sustained her commitment to xerography (or “dry writing,” from the Greek) for 40 years, celebrating its instantaneity, accessibility, and the way in which “copiers bring artists and writers together.” In a 1980 profile in The New Yorker, Hill remarked: “Copies are an international visual language, which talks to people in Los Angeles and people in Prague the same way. Making copies is very near to speaking.”

Hill employed the copier as both a collaborator and a muse. The inspired writing of her 1979 book, Letters to Jill: A catalogue and some notes on copying, serves as a jargon-free primer on the medium and a core resource for the show. The following description of a photocopier that appears on the front of the announcement of her 1978 exhibition at Franklin Furnace is also telling. “This stocky, unrevealing box stands 3 ft. high without stockings or feet and lights up like a Xmas tree no matter what I show it. It repeats my words perfectly as many times as I ask it to, but when I show it a hair curler it hands me back a space ship, and when I show it the inside of a straw hat it describes the eerie joys of a descent into a volcano.”

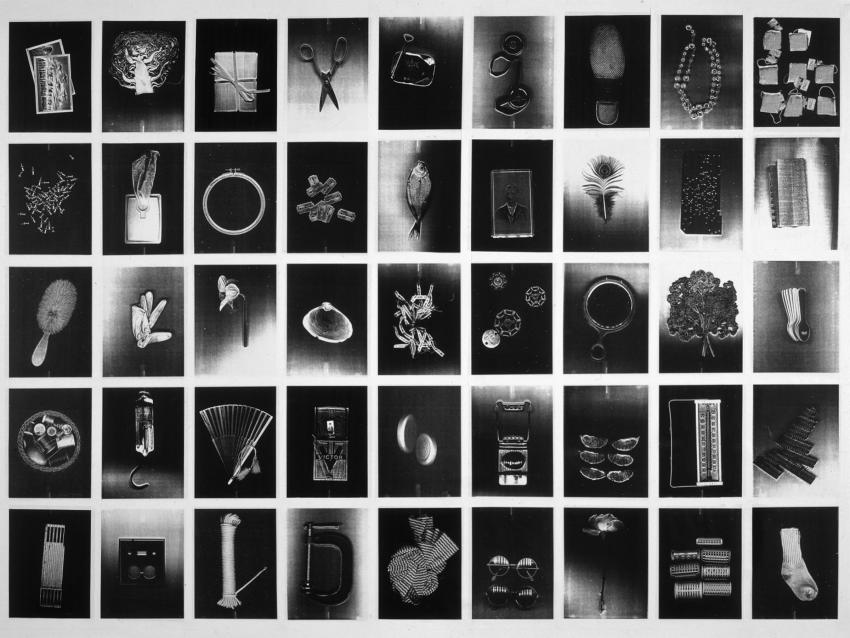

The objects Hill chose to scan are visually transformed yet faithfully convey their intrinsic properties, as well as those of the medium, including its many restrictions. She appreciated the copier’s capacity to duplicate things at life-scale and make “human-vision-sized pictures” with “eye accurate” details. She learned to favor the rich blacks of the IBM Copier II as well as its flaws and distancing effects, which gave the originals Hill isolated on its platen the potential to be read as symbols.

Thanks to a chance encounter on a transatlantic flight with designer Charles Eames in 1977, Hill secured a two-and-a-half year loan of this particular model, which IBM delivered to her home in Stonington, Conn. Direct access to the machine made it possible for her to copy a dead swan she found on a beach near her home, a process that took five weeks and resulted in a suite of 32 captioned prints that suggest a myth of metamorphosis. Hill also used the copier to modify appropriated photographs, which she sequenced into the pictorial narratives that comprise Men and Women in Sleeping Cars (1979) and extend the chilly prose of Impossible Dreams (1976).

Informed by a hieroglyphic symbol language she developed, much of her work from this period sought to fuse text and image into “something other than either.” Unlike many artists who resorted to collage, Hill used the copier as a vehicle for these experiments by applying the formats of the book and the exhibition. By 1979, her interest in testing the limits of the medium inspired her to “photocopy Versailles,” an expansive project that would occupy her for the next 20 years and lead her to work with colored toner, frottage, and photogravure. A selection of initial attempts from this effort—copies of paving stones, an espaliered pear tree, and other materials gathered from the grounds—are included in the exhibition along with a sampling of her publications.

Pati Hill: Photocopier will be accompanied by a catalog and series of public programs that commence with a lecture by exhibition curator Richard Torchia at 6:30 p.m. in the University Commons Great Room preceding the 7:30 p.m. opening reception on February 25.

Additional events will continue through April 24, including a lecture on March 17 at 6:30 p.m. by Michelle Cotton, director of the Bonner Kunstverien (Bonn, Germany). Cotton, who has contributed an essay to the catalog, will discuss Xerography, the international survey exhibition she curated for Firstsite (Colchester, Essex, UK), to honor the 75th anniversary of Chester Carlson’s 1938 invention of the photocopier.

Pati Hill: Photocopier will be presented in the Spruance Fine Art Center and the two galleries of the Commons, marking the first time that all three of these venues will be used to stage a single exhibition at Arcadia.

Major support has been provided by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage.

For more information, including hours and directions, visit gallery.arcadia.edu.

The Spruance Fine Art Center is open Monday through Sunday, and the Commons Gallery is open all week. Hours and directions are available online at gallery.arcadia.edu.

About the artist

Pati Hill (1921-2014) was born in Ashland, Kentucky and raised in Virginia. Demonstrating an interest in writing and art from an early age, she took courses for a year at George Washington University before moving in 1940 to New York, where she became a fashion model. In 1947 Hill relocated to Paris to model the first American collection for couturier Molyneux. By the early 1950s, however, in an effort to concentrate on her writing, she moved to a derelict cottage in the French countryside in Montacher, Yonne, where she completed her first two books, a memoir about that year (The Pit and The Century Plant, 1955) and The Nine Mile Circle (1957), which The New York Times favorably compared to the work of William Faulkner. With the encouragement of George Plimpton, she began publishing her short stories in The Paris Review and in 1957, after she had returned to the United States, took up residence New York City and Stonington, Conn.

In 1959, Hill met publisher and art dealer Paul Bianchini, whom she married in 1960. (Bianchini’s New York gallery was one of the first commercial venues to exhibit Pop art.) In 1962, Hill gave birth to a daughter and published her first book of poems, The Snow Rabbit, illustrated by poet Galway Kinnell. Despite multiple residencies at MacDowell and Yaddo into early the early 70s, Hill did not publish again until 1975 when Slave Days, her first book to include images of her copier prints, was published with the assistance of her Stonington neighbor, poet James Merrill. New York gallerist Jill Kornblee gave Hill five solo exhibitions at her 57th Street Gallery between 1975 and 1979. One of these, Garments, was completed with the inadvertent assistance from IBM thanks to of Hill’s weekend use of the company’s copiers at its New York offices, thanks to the help of supportive friend who worked there.

The following year, Hill was awarded a National Endowment for the Arts Creative Arts Fellowship for her illustrated novel Impossible Dreams. Additional support for Hill’s work from IBM eventually came in 1977 as a two-and-a-half- year loan of one of its Copier II models thanks to the influence of designer Charles Eames. At the conclusion of the loan, Hill re-settled in Paris, where she spent five years photocopying the details of the palace and grounds of Versailles, eventually presenting the resulting large-scale composite works on the site as well as other venues in France. In 1989 Hill and Bianchini opened Galerie Toner in Sens, a small town 75 miles southeast of Paris, where Hill had settled in the late 80s. Dedicated to presenting works made with the photocopier, the venue’s Parisien counterpart opened years later. Hill remained committed to working with the copier and encouraging its use by others, both novices and veterans alike, publishing books and organizing exhibitions until the age of 91.

Venues that have exhibited Hill’s copier prints include the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, Franklin Furnace (in New York City); the Centre Georges Pompidou, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, and the Cabinet des Estampes de la Bibliothèque Nationale de France (in Paris); Musée Lambinet (in Versailles); L’Orangerie des Musées de Sens, France; Gallery Modena, Bologne, Italy; and the Stedelijk, Museum, Amsterdam. Her artwork is in included in the permanent collections of Bayly Art Museum (Fralin Museum), University of Virginia; the Bibliothèque Nationale de France; and L’Orangerie des Musées de France, among others.