Pati Hill: Pioneer, A Groundbreaking Collection Comes to Arcadia

Pati Hill adding toner to IBM Copier II.

Reproduced from “Photocopier Versailles,”

Contact (IBM publication), no. 31 (May 1980).

In the depths of a windowless room on Arcadia University’s campus, tucked away in a nondescript space, stands an IBM photocopier recently arrived from Sens, a small town 75 miles south of Paris.

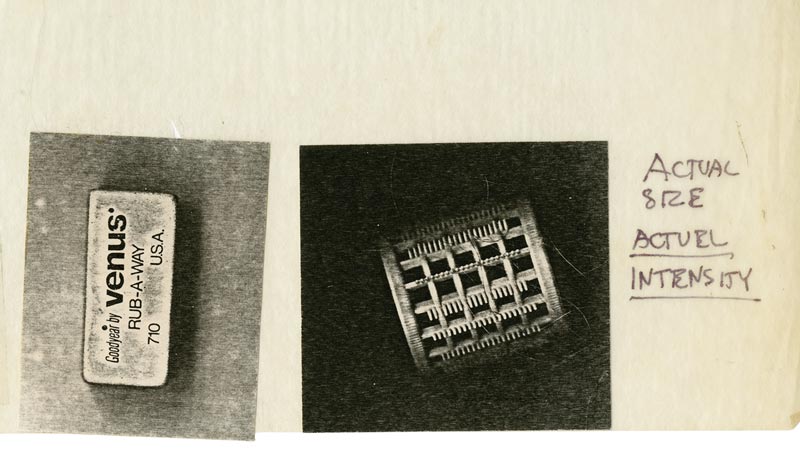

The machine of 1970s vintage is a prize. It belonged to artist and writer Pati Hill, a pioneer in xerography (or “copy art”) who died in 2014 at age 93. Using a model of a copier manufactured by IBM for business purposes, she photocopied everyday items (a pair of gloves, a rubber eraser) and then some, including a dead swan.

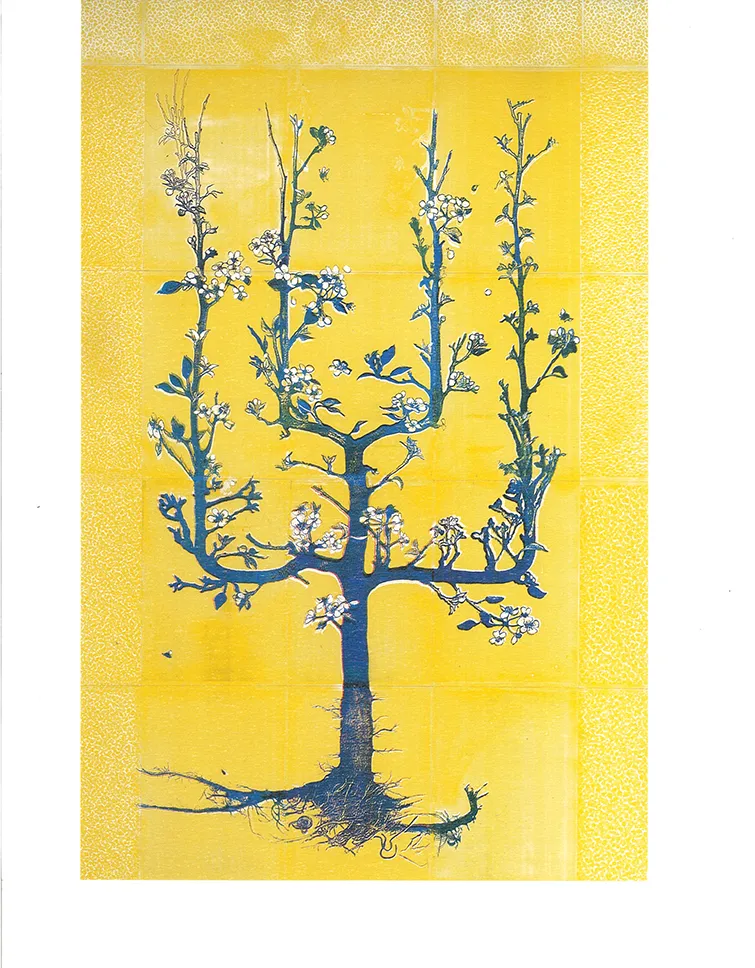

Hill often paired text with images, creating “something other than either,” as she put it. While living in Paris, she made several hundreds of striking images of scarves and even a blooming pear tree from Versailles with this particular 800-pound, floor-standing behemoth, a tool she described as “a found instrument—a saxophone without directions.”

In an adjoining room, an even greater trove awaits—thousands of Hill’s photocopies. “She rarely discarded anything,” says Richard Torchia, director of Arcadia Exhibitions. The brightly lit, 22 x 28 foot, climate-controlled space is ringed by metal shelves, stacked with rectangular cardboard boxes not much larger than a sheet of (11 x 17”) copier paper and filled to the brim with Hill originals poised for archival processing.

This is the Pati Hill Collection, the most authoritative archive of her xerographs, prose and poetry, and personal papers, including a note and questionnaire Torchia wrote when he was 23 years old and smitten by the medium (and, as it turns out, Hill). Nearly 40 years later, he is the de facto protector and promoter of all things Pati Hill. Because of his persistence, by all accounts, her oeuvre of 70 years— documenting a singular view of the evolution of 20th-century art and literature—now resides at Arcadia and, in this centenary of her birth, has achieved critical acclaim through a steady schedule of exhibitions and publications starting in 2016 with a show at the University.

“They were in danger of moldering,” says Judith Stein, a former curator at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. “Dick rescued these from oblivion. He understood from the onset how important she was.”

A Transatlantic Transfer

The path from Sens to Glenside was full of serendipitous turns. Stein tracked down Pati Hill while researching a biography of an art dealer who’d been married to Nancy Christopherson, a close friend of Hill’s.

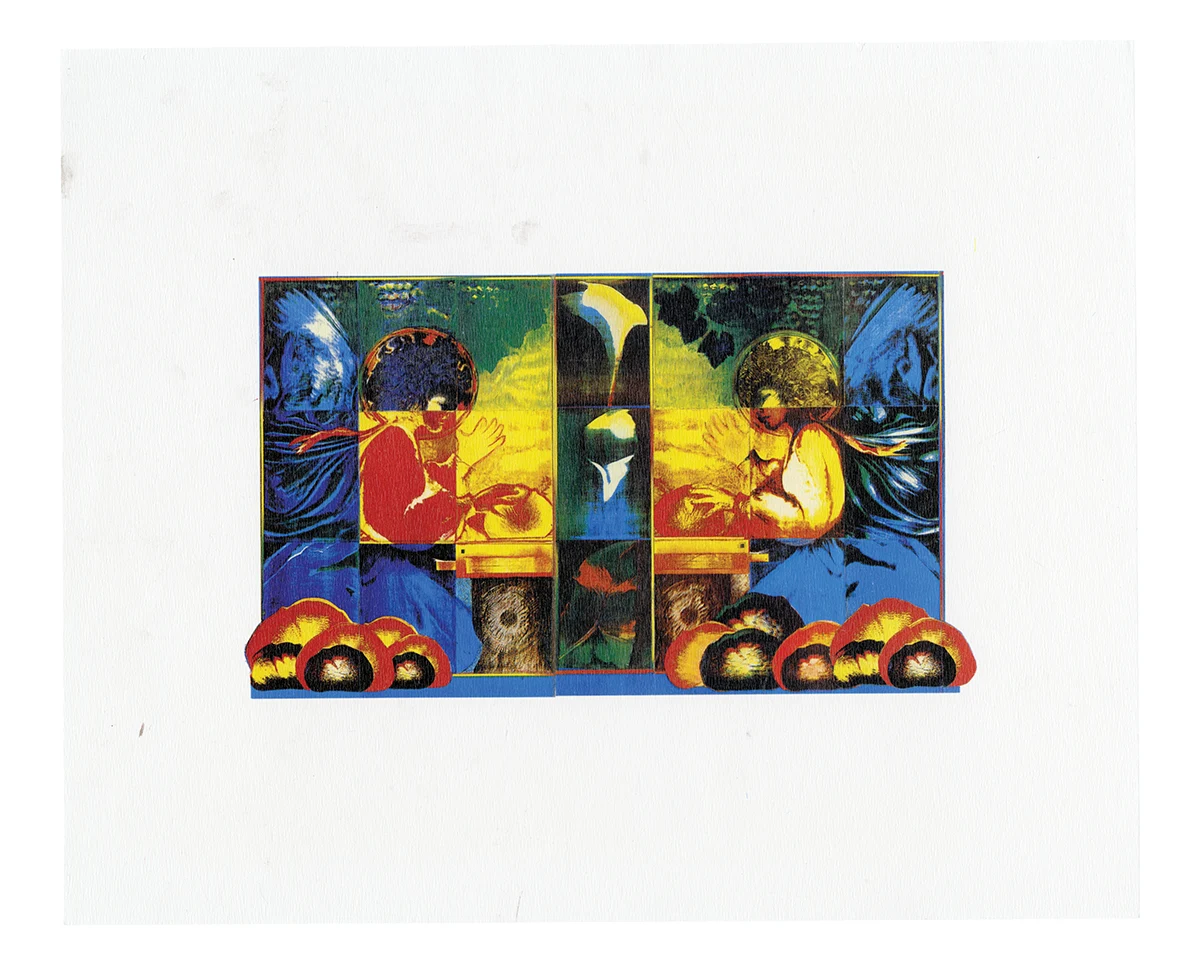

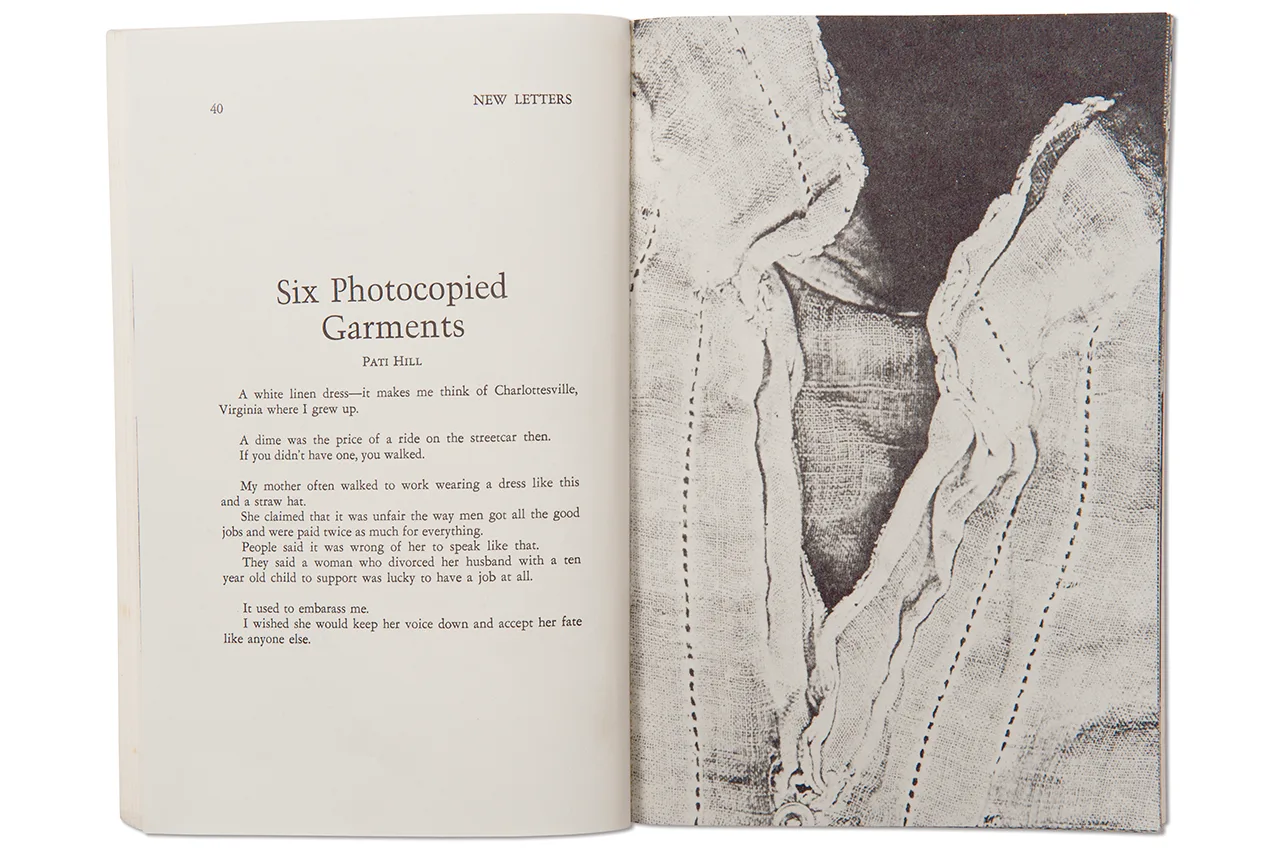

Six Photocopied Garments, 1976, spread from New Letters, vol. 43, no. 1 (1976).

Photo: Philip Flynn.

In 2013, Stein urged Torchia, whom she knew had a deep interest in art made using the photocopier, to reach out to Hill. While in London to attend the presentation of a 35mm film by British filmmaker Tacita Dean that Arcadia had produced and presented earlier that year, Torchia made a detour to Hill’s studio in Sens.

Encouraged by the visit, Torchia developed a successful proposal to The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage to fund a survey documenting the first decade of Hill’s work, which opened in 2016 at Arcadia. After her death, Torchia and Nicole Huard, Hill’s assistant, hustled to find a home for her art and papers. In October 2017, the collection arrived at Arcadia, thanks in large part to a generous donation from Dorothy Lichtenstein, wife of Pop artist Roy and one-time art history student at Beaver College, who served as director of the Paul Bianchini Gallery in New York, one of the first commercial venues to sell Pop art. (Bianchini was Hill’s third husband, and the two women became friends.)

Prior to these events, though, when Torchia was fresh out of Holy Cross College with an English degree, the aspiring writer had an audacious idea: Launch a magazine as an outlet for copy artists. About the same time, a friend gave him Hill’s 1979 book Letters to Jill, which catalogued the first five years of her artwork along with “some notes on copying,” as the subtitle read.

“Right away,” Torchia says, “I was bowled over by the images, including those of the dead swan.”

Torchia recounts a Hill tale punctuated with her grim humor: She found a deceased bird near a local beach in Stonington, Conn., where she lived for many years. Of course, she has to copy it, outside in. Hill takes it to a butcher, has it eviscerated. The guy quips, as Hill tells it, “Swans are good eating as well as good copying.”

A Swan: An Opera in Nine Chapters, 32 stunning black-and-white images accompanied by text that suggests a “myth of metamorphosis,” first exhibited in 1978 at the gallery of contemporary art dealer Jill Kornblee, to whom the pages of Letters to Jill are addressed.

“I was intoxicated by Hill’s prose,” Torchia says of Letters to Jill. “This was the writing I wanted in my magazine.”

Torchia also had fallen hard for copy art. He had no formal art training, but then, neither had Hill. “The photocopier made art-making simple, fast, and inexpensive and open to an impulse that wasn’t so much about skill or virtuosity. All you had to do was think and see.”

Torchia’s interest in the photocopier led to his first curatorial project, a group exhibition exploring prints made with contemporary technology, which originated at the Princeton Art Museum in 1983. Other shows and opportunities followed, including the chance to direct the gallery at Arcadia in 1997.

“The photocopier made art-making simple, fast, and inexpensive…”

– Richard Torchia

A Singular Creative Adventure

Hill also came to xerography by accident. In 1941, after a year at George Washington University, she moved to New York City intent on becoming a writer. To earn a living, she began to work as a fashion model and a year later met the not-yet-world-famous photographer Diane Arbus—then working with her husband managing a commercial photo studio. Arbus became one of Hill’s closest friends.

When Hill’s success as a model threatened to distract from her ambition to write, in 1950, she retreated to the French countryside to live in an abandoned farmer’s cottage for a year. There, she completed her first two books, the memoir The Pit and the Century Plant (1955) and the novel The Nine Mile Circle (1957), the latter drawing comparisons to William Faulkner. Hill also landed an interview with author Truman Capote in the Paris Review, a celebrated literary magazine that featured many major writers and published most of Hill’s early work.

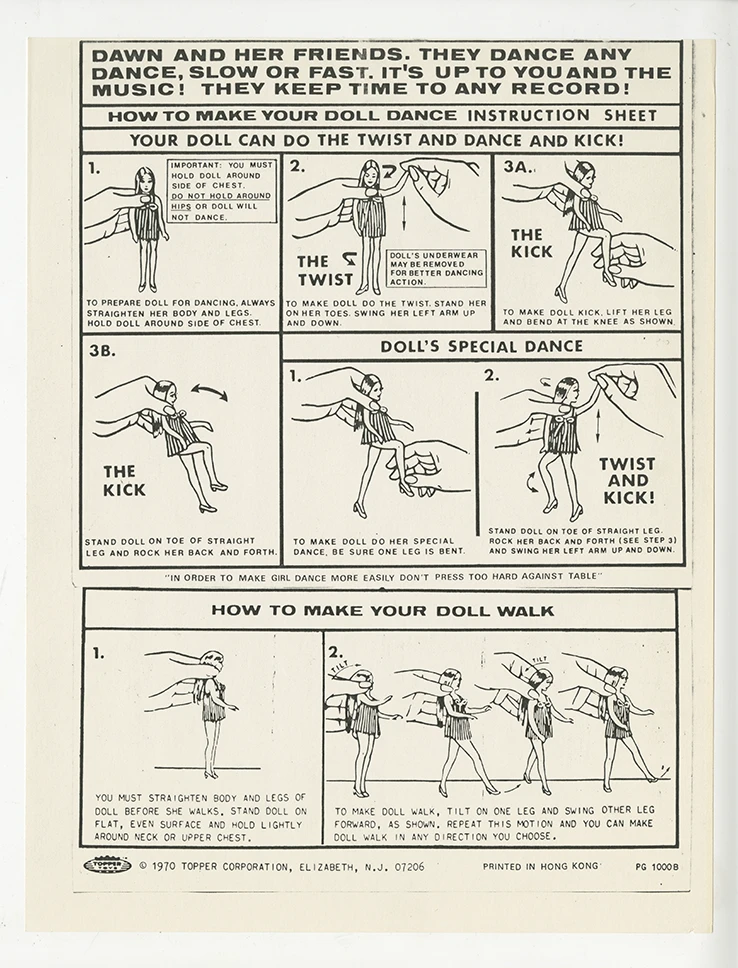

Two other novels and a book of poems, illustrated by lauded poet Galway Kinnell, followed. In 1962, Hill and Bianchini had a daughter, Paola. The rigors of motherhood and housekeeping in Stonington weighed on Hill, and she suffered a fallow period. She did, however, begin collecting what she called “informational art” (charts, “how-to” diagrams, advertisements) as well as objects—her future copy art subjects. One story goes that inspiration came when she was cleaning out a drawer and decided to have the items photocopied as a way to remember them.

Hill modeling in Central Park, c. 1946. Photo: Diane and Allan Arbus Studio,

New York. Courtesy Nicole Huard.

Soon Hill, taken by the exact, 1:1 scale of xerographic reproduction, was monopolizing the IBM machine at a local copy shop, placing all manner of objects on its glass platen with its lid lifted, resulting in lush, black backgrounds. These prints consumed so much toner that she was asked to stop using the machine. She even slipped into IBM’s New York City office and spent a weekend copying, sleeping on the floor and surviving on vending machine snacks.

In 1975, Hill published Slave Days, a collection of poems “about being a housewife” juxtaposed with photocopies of small, household objects. The book was produced with support from Stonington neighbor and Pulitzer Prize-winning poet James Merrill, who was taken by Hill’s pairing of images and verse. Other literary/visual works followed, including a novel illustrated by appropriated, photocopied photographs from more than three dozen sources funded with support from the National Endowment for the Arts. Eventually, she had an IBM copier installed in her Stonington home after designer Charles Eames, who she charmed with her copier work on a flight from Paris to New York in 1977, facilitated a loan for two-and-half years. Hill experimented with moving objects across the glass platen, using colored papers and pouring extra toner into the machine to achieve the rich black backgrounds she wanted. More notoriety followed a 1980 profile in The New Yorker when A Swan was being exhibited at both the Centre Pompidou and in a traveling survey of xerography presented at the Cooper Hewitt Museum in New York, a show covered in the Wall Street Journal in a front-page article that prominently featured Hill and her work.

This attention was momentary, however, and despite maintaining the momentum of her practice, and ongoing advocacy for xerography in the 1990s that took the form of running a gallery with her husband devoted to the presentation of art made with copiers, Hill eluded recognition from the artworld. Torchia cites many reasons, including her relocation to France, her fastidious temperament, and her hybrid artist/author practice. “Hill and her work were hard to categorize at that time. The art world is now much more open.”

Torchia, though, had no such concerns. After their initial visit, Hill said, “This is the first time someone understands my work so well,” according to Huard, who added, “That was very important to her.” Huard, who visited Glenside to help unpack and arrange the collection, says Hill would be pleased with the archive.

Even in this fledgling state as it awaits the touch of a professional archivist, the collection has proven a rich resource. In addition to the acquisition of Hill’s Alphabet of Common Objects, a grid of 45 photocopies, by the Whitney Museum of American Art, it has generated a thesis paper; honors classes; a well-reviewed exhibition at Essex Street, one of New York’s most progressive commercial galleries; exhibits at distinguished European venues for contemporary art; various grants; and numerous students and visitors left in awe. As a repository of artifacts of outmoded communications technology, it has also generated excitement in the conservation community eager to explore ways to preserve and care for the prints.

Hill’s “rigorous experimentation with an IBM copier is one of the great artistic adventures of the mid-20th century,” says Lee Price, director of development at the Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts in Philadelphia who has consulted with the University on grant opportunities to preserve, catalogue, and digitize the breadth of items.

“The collection is the proverbial big fish in a small pond at Arcadia,” he says. “It’s not likely to get set aside or forgotten.”

WORK THAT SPEAKS TO SO MANY

Certainly, the contemporary art scene is deeply interested in Hill now. In 2020 and 2021, galleries in Paris, Munich, and Zurich have exhibited her work, focusing on Hill’s cynical, even dark take on themes of domestic labor. In September 2020, an exhibition at Air de Paris gallery that included Hill’s vast collection of vacuum cleaner advertisements from 1910 to 2010, was celebrated as one of the best in Europe at the time by Frieze magazine.

“Pati Hill: Something other than either” was shown at Kunstverein München in 2020 and has traveled to Kunsthalle Zürich where it remains on view through May 2021. Meanwhile, a group show at the Whitney, Nothing is So Humble: Prints from Everyday Objects, is on exhibit through the spring.

Maurin Dietrich, director of the Kunstverein München, traveled to Arcadia twice to put together a show that has attracted art historians, social scientists, graphic designers, and fashion writers, with some visitors traveling from as far away as Italy and France. “There were so many people interested in the exhibition,” she says. “How beautiful that this work speaks to so many people.”

But perhaps most impactful are the students and faculty that Torchia has inspired with his enthusiasm—not unlike Spruance all those decades ago (see sidebar).

Molly Foster ’19, a Painting and Art History major, says exposure to the archive as an undergraduate shaped her career interests. “It wasn’t until I started working with the collection and Richard that it clicked,” she says. “I love to read. I love research. I love art. All that comes together in this archive.” Now, Foster works as a part-time curatorial assistant for Arcadia Exhibitions, often sequestered in the collection.

A few years ago, when Torchia floated the idea of an honors class tied to the Hill exhibit, Sue Pierce, an Arcadia adjunct professor of English, was immediately on board to co-teach.

Zachary See ’16 also was captivated as a master’s student in English and Literature, especially by Hill’s literary works in the tradition of Southern writers. (Hill was Kentucky born, Virginia bred.) See “found her voice unique” and switched his thesis topic from F. Scott Fitzgerald to Hill. After facilitating the two honors classes that Pierce and Torchia taught on Hill as a teacher’s assistant, See traveled to France several times to conduct biographical research and helped Huard inventory the collection before it was shipped to the U.S.

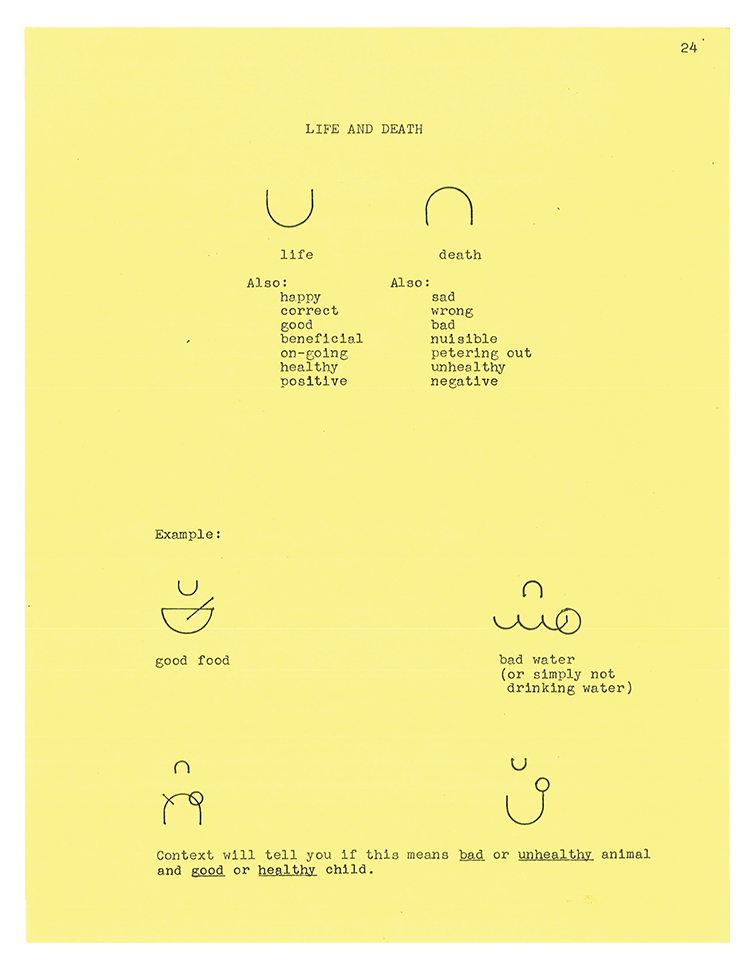

Research by Lindsay Miller ’16 was channeled into the first Pati Hill Wikipedia entry in English. Other students in the honors class took a keen interest in her symbol language, a series of emoji-like glyphs that reflect the way digital media prioritizes images over words. Tessa Paige ’18, along with Miller, contributed a chronology of Hill’s life to the (award-winning) 200-page publication prepared in conjunction with the Arcadia exhibition.

CELEBRATING A CENTENARY

To mark the 100th anniversary of Hill’s birth on April 3, the University will display examples of Hill’s works around campus as part of a concerted effort to increase the Arcadia community’s awareness of the collection, an effort supported by a grant funded from the University to honor innovation. The Whitney sale will fund an archivist for a year or so. But what the collection really needs to realize its full potential is, well, a patron. “In the long term,” says Exhibitions Coordinator Matthew Borgen, “it should be housed in a space on campus designed as a proper archive to make sure these works are preserved indefinitely.”

Brigette A. Bryant, vice president for Development and Alumni Engagement at Arcadia, relishes the possibilities that the archive presents. “It creates a richness that we otherwise wouldn’t have,” she says. “I can’t stress enough what a big deal it is for us to have this collection. My hope is that donors would want to be a part of that.”

Mindful of the goal to make the archive a self-sustaining endeavor, Torchia and his team are doing their best to leverage ongoing interest in Hill’s work from curators, scholars, and publishers in the U.S. and Europe as a means to explore the archive and mine a significant body of unpublished writing that awaits editing and translation, not to mention restoration and eventual digitization. Given the scope and diversity of the material—all the more unique for being as intact and as comprehensive as it is—opportunities abound for students in a surprising range of fields, including library sciences, conservation, communications technology, and language studies, not to mention art and literature.

Celebrating Hill’s centenary may mark the beginning of another century of discovery and innovation. The possibilities extend across academic disciplines and to students, faculty, staff, alumni, as well as members of the regional, national, and international art communities. Securing the Pati Hill collection is yet another historic milestone in the artistic legacy of Beaver College and Arcadia University.

“Hill’s lack of artworld recognition,” said Torchia, “as well as the fact that her life story was never adequately told and appreciated prior to her death, serves as both license and opportunity for Arcadia to assume authority regarding her biography and the narrative of her creative achievement. It is a remarkable responsibility, but one we recognize and are doing our very best to honor.”

Lini S. Kadaba is a journalist based in Newtown Square, Pa., and frequent contributor to Arcadia magazine.

Follow the Arcadia Art Gallery on Facebook and Instagram. For more information on the gallery, go to gallery.arcadia.edu.