First-Gen Resources Are MIA

To anyone who has attended a university for just six weeks, it’s pretty clear that college life is rough. The transition from high school to college can be overwhelming on many levels. From learning new, and often rigorous, material, to managing finances, to navigating university resources, such as tutoring and counseling services, college life can be quite a balancing act.

Now imagine having to balance all of these things as a first-generation college student. And even more burdensome, juggling college as a first-generation student of color at a predominantly white institution (PWI).

A first-generation (first-gen) college student is someone who is the first in their family to attend a higher-education institution. In other words, they are receiving a college education, but their parents or others in the family did not.

PWI’s aren’t always equipped to provide ample resources or services for minority students or first-generation minority students. Yet where first-generation resources are missing in action at many universities, at Arcadia, one club has sought to usher in change.

Launched in September, Melanin in Action (MIA) is Arcadia’s newest club for students of color, dedicated to helping them find pathways to succeeding. Its founders, Aliyah Abraham ’18, Daniel Mack ’18, Tessa Kilcourse ’20, and Elijah Wilson ’19, noticed that there just weren’t enough of…us. There wasn’t a very large body of multiethnic students (though Arcadia is increasing in racial and ethnic diversity), nor enough professors, advisors, counselors, or programs who understood what it was like to be a first-gen student who belongs to racial or ethnic minority.

To be clear, not all students of color are first-generation college students. I do, however, want to highlight the experiences of students who are.

As I mentioned earlier, being able to navigate university resources is a key to getting through college. Asking for help (like seeking a tutor or counselor) can enhance a struggling student’s success, but for students of color, asking a professor or counselor for help can often be terrifying and stigmatizing— especially if the student is doing poorly in a course or is behind on coursework because of the amount of time they may have had to spend working a side job. While struggling to coordinate a full-time job with a full-time education is common to students of all backgrounds, it is only the minority student who is fearful of opening up about such a situation because of the stigma associated with their race or ethnicity.

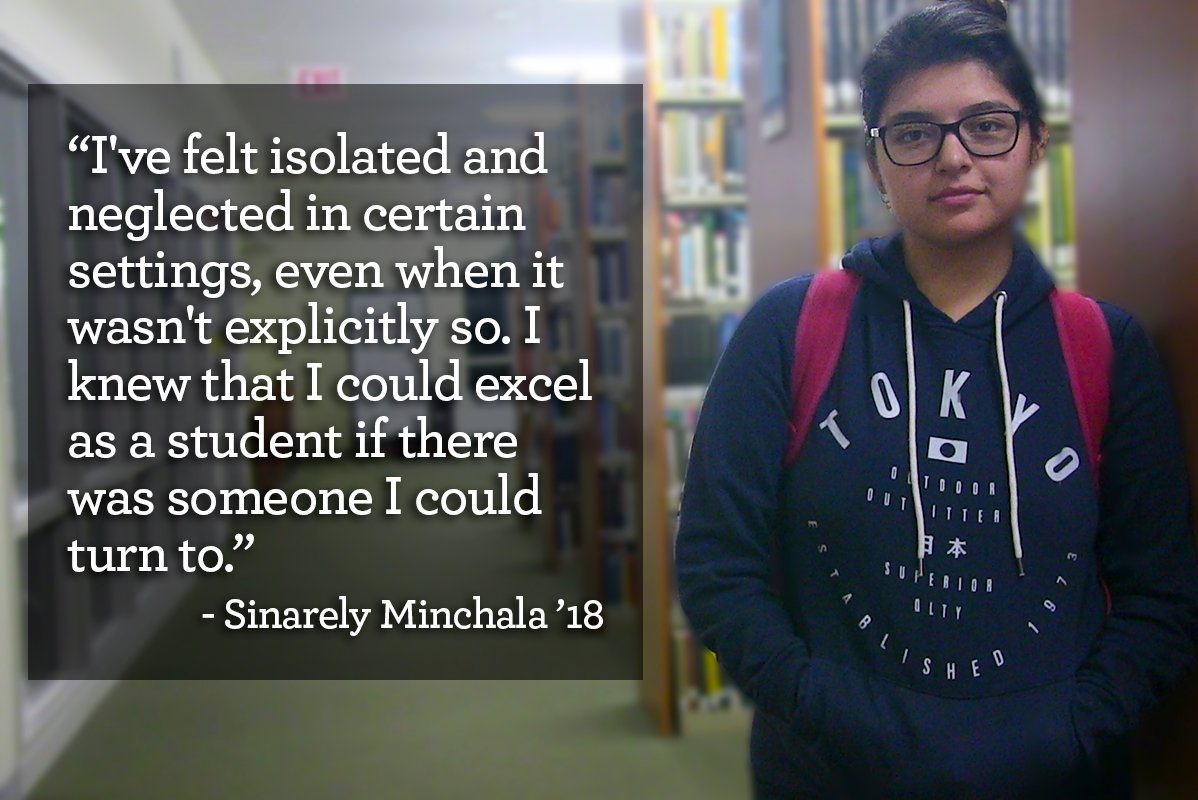

One student, Sinarely Minchala ’18, says “I’ve always felt stigmatized, growing up in an American school system. I’ve felt isolated and even neglected in certain settings, even when it wasn’t explicitly so. I knew that I could excel as a student and reach my fullest capacities if there was someone I could turn to not only for academic advice, but also for personal life advice regarding the struggles surrounding minority students.”

Minchala is certainly not the only minority who has felt like this. While she, and many first-gen minorities, have had their experiences go unseen, MIA certainly sees.

Kilcourse says a club like MIA “is important on campus because there is currently a missing link between students of color and many opportunities here on Arcadia’s campus.” Witnessing how racial and socioeconomic challenges were affecting minority students and their success rates, the four students felt it imperative to create a club that could stand in the gap between these realities.

“In our pursuit of change, we stepped out to raise awareness [of the] things students said to each other but not necessarily to faculty and staff, and I think that is important,” says Abraham.

She is exactly right— that is important. Minority students should be able to share their experiences with faculty. And faculty and other members of college campuses need to be aware of the real issues that minority students and first-gens face in silence.

While a mere student-run club cannot exactly enlist more faculty members that minority students can relate to, what MIA does seek to do is pair students up with alumni who endured similar challenges during their years at university.

MIA is important to me because we gave a voice to the voiceless. Anything that helps one demographic of students helps Arcadia as a whole.

– Aliyah Abraham ’18

Melanin Not a Requirement

In addition to providing first-generation students with a community that they can turn to, MIA is devoted to breaking down racial stereotypes that may exist on college campuses and that are rampant in our society.

For example, it is a tragic misconception that students of color at private or elite universities are admitted into their higher-education institutions by way of affirmative action— or that all black male students attending a university are there because they excel in football or basketball. Why can’t it just be assumed that racial and ethnic-minority students are just as academically qualified to be at their universities as their non-minority counterparts?

Things like this come up often in meetings at MIA.

In fact, a regular meeting at MIA consists of active discussion on current events that pertain to race, racism, and racial stereotypes. Students often share stories of the ways in which they’ve been victims of racism and racial stereotypes and the central question each time: How can we change this?

One way that we can help eliminate stereotypes surrounding minorities and first-generation minority students on campus is by educating and forming allies with the racial majority. In other words, having a greater attendance of white students and faculty.

Members of Melanin In Action on Haber Green.

“In any movement there has been allies that are not of color,” says Abraham. “It is just as important to make white students and faculty more educated regarding issues of race as it is students and faculty of color. The more we are educated as a community, the more we will be compassionate and accepting of each other regardless of our appearance and ethnicity.”

It may come as a surprise to some that a club called Melanin in Action would be imploring students of the lighter variety to come and link up arms, but that is actually MIA’s motto — that melanin is not a requirement!

In fact, movements like MIA desperately need partnership from our white-folk. Traditionally, when white students advocate for students of color, other white students and white administration are more likely to hear their voices before they would a minority student’s. “This is because many people in positions of privilege enjoy the status quo,” says Kilcourse, MIA’s (white) public relations manager.

Daniel Mack adds: “There are times when we cannot relay a message to a certain person, who might be more willing to listen to someone who looks like them than to listen to someone who doesn’t.”

With the club having only been active for less than two months, change is already beginning to form on Arcadia’s campus.

“I can’t count on one hand the amount of times that a student has come up to me, thanking me and my team for MIA’s creation. I walk around campus and see so many familiar faces, people who truly needed a safe space have now found it in MIA and are happy to interact with the executive board daily,” Kilcourse explains.

That may sound like a small victory, but having a space where our voices can be heard is making a huge difference in the lives of first-generation minority students.